Evolution

Evolution

Eat, Bubbeleh, Eat!

From the annals of peculiar nature stories comes this news item, seemingly designed to distress the Jewish mother in all of us. In captivity in Japan, a giant isopod has refused to eat for four years. The creature, jauntily named “No. 1” by its keepers at the Toba Aquarium in Mie Prefecture, has turned down all nourishment since January 2, 2009, when it gobbled a horse mackerel.

Takaya Moritaki, in charge of feedings, testifies that it merely pretends to eat by poking at and rubbing its face in proffered meals of raw mackerel. (Perhaps it’s concerned by recent accounts of widespread false commerical labeling of seafood, reported by the advocacy group Oceana, a deceptive practice committed in particular by sushi restaurants.)

“I just want it to eat something somehow. It’s weakened in this state,” Mr. Moritaki said holding his head in his hands.

It never writes. It never calls either.

The animal looks like an enormous pill bug and was caught originally in the Gulf of Mexico. The Japan Daily Press, which interviewed Mr. Moritaki, suggests that not eating is an adaptation to its undersea environment, where you never know where your next meal will come from. Yet not eating when food is repeatedly presented to you seems like a very strange survival adaptation. For more, see the NPR story. There’s another interesting evolutionary angle on the giant isopod, which goes by the formal scientific name Bathynomus giganteus. It lives in deep waters off Australia, Mexico and India, where it has remained basically unchanged in these widely separated environments for more than 160 million years. Given Darwinian expectations, shouldn’t the giant isopod populations have diverged notably in that time?

There’s another interesting evolutionary angle on the giant isopod, which goes by the formal scientific name Bathynomus giganteus. It lives in deep waters off Australia, Mexico and India, where it has remained basically unchanged in these widely separated environments for more than 160 million years. Given Darwinian expectations, shouldn’t the giant isopod populations have diverged notably in that time?

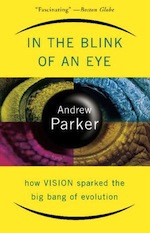

Actually, Bathynomus provided a piece of evidence for Oxford zoologist Andrew Parker in his book In the Blink of an Eye, which offers a clever attempted solution to the enigma of the Cambrian explosion. Parker argues that what set off the Cambrian event, 543 million years ago, leaving the world with 38 animal phyla where there had previously been only three, is the “discovery” of vision by something soft-bodied that came before the most iconic of Cambrian animals, the trilobite.Vision sparked the rapid evolution of numerous new animal body plans — which also explains, writes Parker, the evolutionary stasis of Bathynomus, living as it does so deep down in the dark waters. In the absence of light, evolution lacks a key stimulus. It’s a novel theory, if vastly inadequate and question-begging, but you have to give credit to Andrew Parker who properly recognizes the scope of the riddle he’s up against.

He writes, “Until now we have been without an acceptable explanation for this extraordinary burst of evolution — there is strong evidence against all the contending theories put forward.” It’s either his own theory or an explanatory void, at least as far as unguided Darwinian processes are concerned.

Chew on that.