Evolution

Evolution

Free Speech

Free Speech

News Media

News Media

The Textbooks Don’t Lie: Haeckel’s Faked Drawings Have Been Used to Promote Evolution: Miller & Levine (1994) (Part I)

|

Since Randy Olson’s film “Flock of Dodos” was shown on Showtime this week, we thought it worth re-highlighting material discussing Haeckel’s fraudulent embryo drawings. “Flock of Dodos” and Randy Olson’s statements have tried to rewrite history by claiming that Haeckel’s fraudulent embryo drawings have never been used in modern textbooks to promote evolution in the present day. His argument is that either (1) the drawings were never in textbooks, or, when that argument doesn’t work, he falls back on his old claim that (2) the drawings were in textbooks, but they were used only to provide a historical context of evolutionary thought. Both arguments are easily demonstrated to be false.

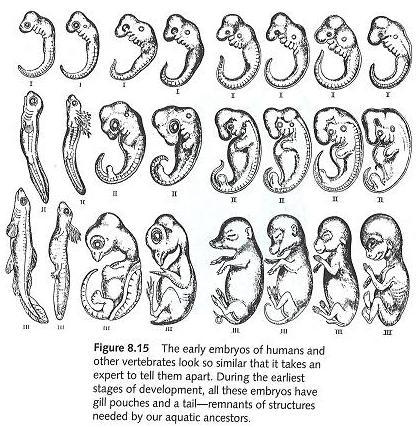

Darwinian biologist Ken Miller has authored many biology textbooks. His first textbooks (from the early 1990s) used Haeckel’s fraudulent embryo drawings and blatantly promoted the idea that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. This is seen below in the re-printed text and scan of page 162 from Miller’s 1994 textbook Biology: Discovering Life with the caption also shown (see here for the full scan of page 162):

To Miller’s credit, he fixed later editions of his textbooks–he took out Haeckel’s drawings and replaced them with real embryo photographs, and he also stopped promoting recapitulation theory. Like many Darwinists, however, Miller then tried to rewrite history and pretend that these mistakes had not been promoted by biologists for many decades.

Randy Olson would have you believe that when Haeckel’s drawings are used, they are only given to provide some kind of “historical perspective on biology” or “historical context” and that they are not promoted as actual fact in the present day. Miller & Levine’s 1994 version of Biology: Discovering Life demonstrates how Olson’s claim is false:

Darwin and his contemporaries knew that early embryos of many animals look nearly identical and that the earliest stages of development in “lower” animals seem to be repeated in the development of “higher” animals such as ourselves (Fig. 8.15). Darwin realized that the similar developmental paths followed by animal embryos make sense if all of us evolved long ago from common ancestors through a series of lengthy evolutionary changes.

These striking embryological similarities led some of Darwin’s contemporaries (though apparently not Darwin himself) to believe that the embryological development of an individual repeats its species’ evolutionary history.

Why, then, should the embryos of related organisms retain similar features when adults of their species look quite different? The cells and tissues of the earliest embryological stages of any organism are like the bottom levels in a house of cards. The final form of the organism is built upon them, and even a small change in their character can result in disaster later. It would hardly be adaptive for a bird to grow a longer beak, for example, if it lost its tongue in the process.

The earliest stages of the embryos life, therefore, are essentially “locked in,” whereas cells and tissues that are produced later can change more freely without harming the organism. As species with common ancestors evolve over time, divergent sets of successful evolutionary changes accumulate as development proceeds, but early embryos stick more closely to their original appearance.

(Joseph S. Levine & Kenneth R. Miller, Biology: Discovering Life, pg. 162 [2nd Ed., D.C. Heath, 1994])

Miller was clearly promoting Haeckel’s famous idea that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, as he argues that “the embryological development of an individual repeats its species’ evolutionary history,” and that animals evolve by simply tacking on new stages of development to old ones, which are locked in.

Before Darwinists object by claiming that Miller is merely discussing the history of evolutionary thought and the views of “Darwin’s contemporaries,” I point out two important facts:

(1) The quoted text comes from a section titled “DATA SUPPORTING THE FACT OF EVOLUTIONARY CHANGE” (emphasis in original) and a sub-section titled “Similarities in Anatomy and Development.” (pg. 162)

(2) There is no indication anywhere in the text that any of these ideas are wrong or that they are no longer believed. The reader is left with the distinct and unambiguous impression that this is how vertebrate development works.

It seems that Darwinists like Olson are simply wrong to argue that these drawings and ideas have not been promoted in modern textbooks. As one example, keep in mind that during the Dover trial, Miller testified that at its peak usage, students in “more than 200 colleges and universities around the country” read his early textbooks like this one. (Day 1 am testimony, pg. 41) Yet Darwinists are now denying that any of the ideas in these textbooks, shown here before your very eyes, have ever been promoted in modern textbooks.