Evolution

Evolution

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

A Special Status for Science?

Over at The Atlantic, Paul Bloom, the Brooks and Suzanne Ragen Professor of Psychology at Yale University, writes about the differences between science and religion — their epistemological roots. As David Klinghoffer noted earlier, Bloom’s particular thesis is that science should be given special status because its basis is in experimental fact rather than belief in an authority.

He begins by saying that most of us would be hard pressed to give reasons for our beliefs about religion, politics, economics, even science. So we take things on faith, because we believe that the people whom we view as authorities speak truth.

Bloom says:

… [M]uch of what’s in our heads are credences, not beliefs we can justify — and there’s nothing wrong with this. Life is too brief; there is too much to know and not enough time. We need epistemological shortcuts.

But then he goes wrong. He sets up a special category for science and the nature of its authority, based on an idealized view of how things work.

…[S]cientific practices — observation and experiment; the development of falsifiable hypotheses; the relentless questioning of established views — have proven uniquely powerful in revealing the surprising, underlying structure of the world we live in, including subatomic particles, the role of germs in the spread of disease, and the neural basis of mental life…

[S]cience establishes conditions where rational argument is able to flourish, where ideas can be tested against the world, and where individuals can work together to surpass their individual limitations. Science is not just one “faith community” among many. It has earned its epistemological stripes. [Emphasis added.]

Yes, science has been uniquely powerful in unraveling the inner workings of the world. But there are continuing areas of mystery that materialistic science cannot address. I offer Thomas Nagel’s Mind and Cosmos as evidence. There is more to life than molecules, despite what Bloom apparently thinks.

Two additional things need pointing out. First, scientists are just as prone to credences as others are. There’s just too much to know for anyone to grasp it all. I don’t know limnology. I can’t classify beetles. Most limnologists probably don’t know much molecular biology. And a scientist can be a world expert on beetles but know nothing about DNA sequencing. We rely on the authority of textbooks and professors.

Second, one of the biggest credences in biology today is evolutionary theory. Most scientists accept what they have been taught — they rely on the authority of their teachers. Few make the effort to investigate for themselves the strengths and weaknesses of the theory of evolution.

What does this make of consensus science? Does it justify the persecution of scientists with legitimate questions and evidence against the theory? After all, according to Bloom, science is supposed to be a place where rational argument is able to flourish, where ideas can be tested against the world, and where the relentless questioning of established views can take place.

Let it be so.

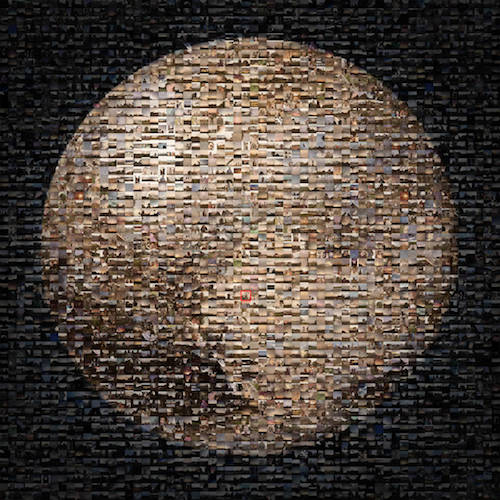

Image credit: “Pluto Time” Mosaic via NASA/JPL.