Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Two Critics of Intelligent Design Prefer Darwin’s Path as a Science Thinker; We Can Identify

One of the criticisms you hear about intelligent design is that ID advocates analyze ideas rather than doing research in a lab. (I’m phrasing that in a polite way.) While ID scientists do indeed perform experimental research, it’s true that weighing explanations for the origin of biological information is a sine qua non, and that need not be done at a lab bench. In the case for ID, reasoning is the key.

So it’s interesting to read candid admissions from two scientists bitterly opposed to ID that they find thinking and writing about science much the most interesting part of being a scientist.

Jerry Coyne (Why Evolution Is True) announced that he’s retiring at age 65 from his post at the University of Chicago and assuming the title of emeritus professor. That’s in part because he finds research less rewarding and wants to turn to writing for a popular audience:

[F]inding truly new things — things that surprise and delight other scientists — is very rare, for science, like Steve Gould’s fossil record, is largely tedium punctuated by sudden change. And so, as I began to look for more sustaining challenges; I slowly ratcheted down my research, deciding that I’d retire after my one remaining student graduated. That decision was made two years ago, but the mechanics of retirement — and, in truth, my own ambivalence — have led to a slight delay. Today, though, is the day.

What am I going to do now? Well, I’m not going to take up golf, which I always found a bit silly. I won’t do any more “bench work” — research with my own hands — but I’m not going to abandon science. I will still write about it, both on this website and in venues like magazines and their e-sites, and I’m planning a popular book on speciation. Writing, for me, is the New Big Challenge, and one that can never be mastered. My aspiration is to write about science in beautiful and engaging words, and to find my own voice so that I’m not simply aping the popular science writers I admire so much. That is a challenge that will last a lifetime, for there is never an end to improving one’s writing.

I found this a little concerning to hear — retirement, if you can avoid it, is not necessarily a good thing. No doubt Coyne has thought his plans over carefully. But writing about science for a general readership is indeed a high calling and he’s a good writer.

Meanwhile another Darwin crusader, Larry Moran (Sandwalk), chimes in to agree:

For me, the pace of discovery in the lab was far too slow. Yes, it’s true that you can be the very first person ever to see something that nobody has ever seen before but those “somethings” are often trivial. I learned that there was a heck of a lot that I didn’t know but other people did. Furthermore, I needed to know all that stuff before I could really interpret my own lab results.

It was far more efficient, and far more exciting, for me to learn facts and information from others than to try and discover something truly important in my own lab.

That’s why I decided to concentrate on writing, especially biochemistry textbooks. It was my opportunity to learn about everything and my opportunity to teach others about what was important and what was not important. It was my opportunity to think about biochemistry and evolution. That was much more satisfying, intellectually, than the tedium of everyday lab work. I was cocky enough to believe that I, personally, could contribute more to science through theory (and teaching) than through working at the bench.

As it turned out, I found far more ways of “seeing the existing world,” as Jerry puts it, though reading, thinking, and teaching than I ever did by cloning a gene and studying its expression. So far, none of those ways are terribly original but they’re at least new to me. And many of them are new to all the people around me who I keep pestering whenever I come across something interesting.

Nowadays, the tedium of stasis in everyday science isn’t the only problem facing young scientists. There’s also the tedium of grant writing and the tedium (and stress) of not getting a grant to keep your lab running. Perhaps they should get out of that rat race. We need more thinking in science and not more ChIP assays or RNA-Seq experiments.

More “thinking in science” to enliven a field plagued by “stasis”? Ditto on that, Professor Moran.

In discussing our new documentary short, The Information Enigma, I wrote the other day about the three ways that ID theorists take inspiration and direction from the example of Charles Darwin. One of them is exactly on this point:

In the video, philosopher of biology Stephen Meyer explains how ID differs from a stereotype of the scientist at her lab bench performing experiments. ID scientists do experiments too, uncovering evidence for design, but the case they make is, like Darwin’s argument in The Origin of Species, fundamentally an argument from the evidence left behind by life’s history. As Dr. Meyer puts it, like Darwin’s monumental work, it is “forensic” in style, employing a “historical scientific method” that involves weighing competing hypotheses, or explanations, against each other.

Let’s all agree that if Darwin did science, so do Dr. Moran and Dr. Coyne, and so do ID theorists, shall we?

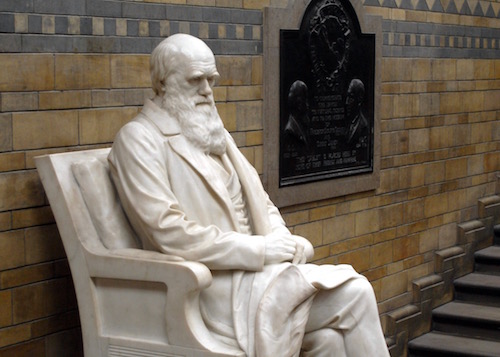

Image credit: Patche99z (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons.