Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Evolution

Evolution

Human Origins

Human Origins

Save Your Brain: Skip Luc Besson’s Fantastical Lucy

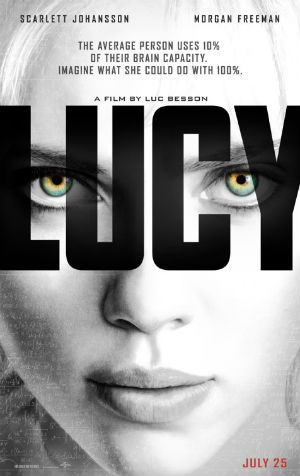

Recently I was referred to see the new sci-fi movie Lucy starring Scarlett Johansson and Morgan Freeman, largely because of its strong emphasis on biological evolution and transhumanism. The movie has made an impressive showing at the box office, earning over $200 million worldwide on a production budget of only $40 million. Reviews at Rotten Tomatoes are tepid but not terrible with only 65 percent of critics endorsing the movie, and only 48 percent of the audience recommending it. Warning: spoilers ahead.

Recently I was referred to see the new sci-fi movie Lucy starring Scarlett Johansson and Morgan Freeman, largely because of its strong emphasis on biological evolution and transhumanism. The movie has made an impressive showing at the box office, earning over $200 million worldwide on a production budget of only $40 million. Reviews at Rotten Tomatoes are tepid but not terrible with only 65 percent of critics endorsing the movie, and only 48 percent of the audience recommending it. Warning: spoilers ahead.

In the movie, Lucy (played by Ms. Johansson) is an innocent young girl living in Taipei who gets abducted by drug traffickers and coerced into helping them. Bad guys with a drug cartel implant in her abdomen a sealed plastic bag full of a potent drug called CPH4, which she is then supposed to smuggle to some destination. There it will be surgically removed and sold. However, on the way she encounters more nasty characters who kick her in the stomach, causing the bag to burst open, spilling the blue crystalline drug into her body.

Though CPH4 is not a drug in the real world — director Luc Besson explains in an interview — it is a real molecule, produced by pregnant women and having important effects upon a developing baby. I leave it to others to peer-review his science, but the story from there on is clearly fictional.

You see, Lucy’s overdose causes her to use more of her brain than the average 10 to 15 percent that (as one often hears) humans normally use. This endows her with all kinds of superintelligent, telekinetic, supernormal powers, like the ability to manipulate her own body in amazing ways, manipulate other people, manipulate matter, travel through time, and ruin the schemes of Taiwanese drug lords. All kinds of mayhem ensues.

Morgan Freeman plays a professor who has conceived hypotheses about what might happen to a person if she started to use more than 10-15 percent of her brain. Lucy confirms and surpasses his predictions. Here’s where the evolutionary connection comes in, starting with the parallel between Johansson’s Lucy and Lucy the famous australopithecine.

The film opens with a scene of the ancient Lucy, drinking water from a river. In another early scene, the boyfriend of Johansson’s Lucy tells her that he went to a museum and found that Lucy was the name of the first woman. Just as that Lucy was supposedly a step in our evolution, in that she purportedly used more of her brain than her ancestors did, so Scarlett Johansson’s Lucy is a further evolutionary step. Lucy the australopithecine makes additional artsy appearances throughout the movie.

This is the main message: that transhumanism is a reality, and humans will be able to continue their prior evolution and entirely surpass our current stage of intelligence. Human technology — in this case through drug use – might be the key to enable humans to reach their maximum intellectual potential.

Or not.

You’d never know it from Mr. Besson’s treatment of the subject, but it’s a complete myth that humans only use 10 percent of our brains. From Scientific American:

Though an alluring idea, the “10 percent myth” is so wrong it is almost laughable, says neurologist Barry Gordon at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore. Although there’s no definitive culprit to pin the blame on for starting this legend, the notion has been linked to the American psychologist and author William James, who argued in The Energies of Men that “We are making use of only a small part of our possible mental and physical resources.” It’s also been associated with Albert Einstein, who supposedly used it to explain his cosmic towering intellect.

The myth’s durability, Gordon says, stems from people’s conceptions about their own brains: they see their own shortcomings as evidence of the existence of untapped gray matter. This is a false assumption. What is correct, however, is that at certain moments in anyone’s life, such as when we are simply at rest and thinking, we may be using only 10 percent of our brains.

“It turns out though, that we use virtually every part of the brain, and that [most of] the brain is active almost all the time,” Gordon adds.

This alone topples the movie’s narrative about evolution.

Most likely, Lucy the australopithecine used just as much of her brain as we use of ours. Her brain, by the way, was about the size of a chimpanzee’s, and it was wired differently from ours. The maximal potential use of Lucy’s brain was fundamentally different than our maximal potential use. Lucy might have used 100 percent of her brain, and she still wouldn’t have the capacity to talk, compose music, or write sci-fi movie scripts.

The origin of human beings involved a massive increase in cognitive ability compared to ape-like species, on a scale that we still don’t understand. The difference isn’t explained by saying we use “more of the brain.” In fact, we know so little about how the human brain works that if anyone tells you he knows how human intelligence evolved, tell him he needs to get his own brain checked out. On this matter, I tend to agree with MIT professor Noam Chomsky:

[I]t is almost universally taken for granted that there exists a problem of explaining the “evolution” of human language from systems of animal communication. However, a careful look at recent studies of animal communication seems to me to provide little support for these assumptions. Rather, these studies simply bring out even more clearly the extent to which human language appears to be a unique phenomenon, without significant analogue in the animal world. If this is so, it is quite senseless to raise the problem of explaining the evolution of human language from more primitive systems of communication that appear at lower levels of intellectual capacity. … There is no reason to suppose that the “gaps” are bridgeable. There is no more of a basis for assuming an evolutionary development of “higher” from “lower” stages, in this case, than there is for assuming an evolutionary development from breathing to walking; the stages have no significant analogy, it appears, and seem to involve entirely different processes and principles. … As far as we know, possession of human language is associated with a specific type of mental organisation, not simply a higher degree of intelligence. There seems to be no substance to the view that human language is simply a more complex instance of something to be found elsewhere in the animal world. This poses a problem for the biologist, since, if true, it is an example of true “emergence” — the appearance of a qualitatively different phenomenon at a specific stage of complexity of organisation.

OK, but why am I taking a silly movie so seriously?

First, there’s a reason why Lucy the movie has done so well. Its premise taps into what a lot of people think about how humans evolved, and how we might evolve further. They assume that evolving human intelligence was a snap — just as easy as (supposedly) unlocking the potential to use more of your brain.

Second, lots of people hope that achieving immortality — a forthcoming “step” in “human evolution” — might be as simple as empowering our brains and consciousness to do more through technology. The movie Lucy sheds some light on tranhumanism’s goals, which our colleague Wesley J. Smith describes as follows:

Transhumanism is selfish, all about me-me, I-I. Its goal is immortality for those currently alive, and the right to radically remake themselves and their progeny in their own image.

For now, I have to say that my previous opinion of transhumanism as a materialistic religion — or perhaps better stated, a worldview that seeks to obtain the benefits of religion without submitting to concepts of sin or the humility of believing in a Higher Being — is being substantially borne out.

These are good descriptions of the philosophical undercurrents in Lucy. True, the protagonist helps cure her roommate’s disease, but what is one of the first things Lucy does with her increased brain capacity? She goes and kills a bunch of the Taiwanese drug lords who had previously been harassing her. The body count that Scarlett Johansson produces in the course of the movie is extremely high. If Lucy represents the next step in human evolution, I’d prefer to keep my brain at its current level of activity.

I love science fiction and there are plenty of sci-fi shows and movies I enjoy watching despite their having an ideological message that I disagree with. So I was more than open to liking Lucy. Unfortunately the movie just doesn’t do it for me. These reader comments from Rotten Tomatoes capture my feelings (if somewhat inarticulately):

The type of bafflingly stupid movie that believes [itself] to be much smarter than it ever comes close to [being], incapable of raising any minimally constructive philosophical questions beyond the most obvious pseudo-metaphysical silliness and with Johansson in a terrible performance.

Actually Johansson’s performance wasn’t that bad. More:

This movie worries that humanity is wasting its potential, which is a bizarre fear for a movie that has this many nonsensical shootouts. But that’s what [is] on Besson’s mind: the Big Bang and bang-bang.

Another:

In this pile of adolescent heavy-metal-deep pseudo-sci-fi philosophy, the meaning of humanity (or lack thereof) depends on how “cool” something looks onscreen.

Another:

The movie’s title character may find her brainpower increasing as the running time counts down; chances are you’ll feel like your own IQ levels are dropping just as rapidly as you watch it.

The movie is fiction, but that last comment is certainly true. I suspect these low ratings stem from the fact that this was a science fiction movie aimed at an audience that loves science, and that found the proportion of fiction a bit overwhelming.