Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes Against the Backdrop of Human Exceptionalism

Like Wesley Smith, I saw Dawn of the Planet of the Apes over the weekend and can report, in agreement with him, that it appears not to relish the decimation of the human race. Good! In that sense, as Wesley says, it doesn’t fit neatly under the "War on Humans" heading, as some pre-release reviews hinted and as I earlier speculated that it might.

Like Wesley Smith, I saw Dawn of the Planet of the Apes over the weekend and can report, in agreement with him, that it appears not to relish the decimation of the human race. Good! In that sense, as Wesley says, it doesn’t fit neatly under the "War on Humans" heading, as some pre-release reviews hinted and as I earlier speculated that it might.

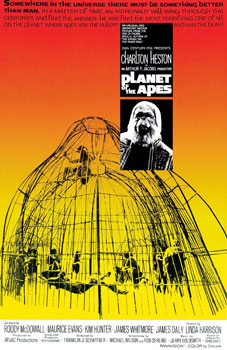

Yet it very much reflects a culture at odds with what Wesley calls human exceptionalism. That comes across most clearly if you compare Dawn with the original movie that got the franchise rolling. The 1968 Planet of the Apes film is typically classified as science fiction, not incorrectly, but it’s also a horror movie.

What is horror? I mean genuine horror? More than just scary, and not necessarily supernatural, horror refers to the depiction of things that should not be because they violate profound assumptions about life, death, society, relationships, the world, or the cosmos. In that sense, horror is a conservative kind of art: it depends on our being sufficiently attached to norms that their violation, really their desecration, makes you flinch.

Arguably, horror even assumes intelligent design — some purpose and order woven into the fabric of the universe that, when desecrated, produces a shudder. If materialists are right and nature just churns away without purpose, if the universe haphazardly produced what we consider normal, there’s really no place for horror. What we think of as normative is only that by convention or chance.

The greatest scene in the original Planet of the Apes is the unforgettable one at the beginning. A tribe of primitive, mute humans in loincloths are overtaken and hunted by uniformed gorillas on horseback. The gorillas shoot and capture the humans, then photograph themselves smoking cigars, laughing, and posing with the bound captives.

Though the costumes and other special effects aren’t remotely as sophisticated as what we expect in 2014, the impact is terrific and not stale in the least even 46 years later, at least not to me. Why? Because at heart many of us, though far from all, still find it horrific to imagine our relationship with animals, including apes, reversed.

The film goes on in the same key. Despite minor concessions to campiness, it is horror-inducing right up to the last moment when Charlton Heston as Taylor discovers the ruins of the Statue of Liberty. He realizes he is back on Earth centuries after human civilization destroyed itself. A fantastic movie.

The 1968 Apes film takes human exceptionalism for granted. The fact that, in the story, we humans so spectacularly debased our special role as inheritors of civilization — even losing the power of speech! — forms the background to everything that makes it powerful.

That’s very, very different from Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, and the difference speaks volumes. Unlike Wesley, perhaps, I enjoyed the new movie. Listen to Michael Medved’s review, which is basically how it came across to me.

But Dawn is firmly in the survival-adventure-war genre, not horror. Seeing San Francisco in ruins is melancholy, also picturesque, but we are not given to understand that there’s any fundamental violation of anything in seeing chimps speak, ride horses and shoot guns at human beings. Evolution simply got speeded up a bit, thanks to the use in lab experiments of a fictional virus.

The old assumption that humans are different from animals has been transcended, or politely stepped around, here. The villains (Gary Oldman as Dreyfus, Toby Kebbell as the smoldering, scarred bonobo Koba) are dangerous because they believe their species to be exceptional. Dreyfus screaming about how the apes are just "animals" is diagnostic of what the movie sees as being wrong with him.

By contrast, the heroes (Jason Clarke as Malcom, Andy Serkis as the chimp leader Caesar) are egalitarians, with Caesar at one point reflecting on how he used to think apes are better than humans, but sees now that they are really the same. The structure of the story underlines the point is, with the parallel ape and human bad guys and good guys.

You couldn’t make a movie like the 1968 Planet of the Apes today because so much of our culture no longer buys the premise that there’s anything special about human beings, any inherent dignity or unique source of responsibility to the world.

That doesn’t make Dawn a bad movie, though it’s a much shallower entertainment than its predecessor. Certainly, it is a sign of the times.