Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Cosmos Episode 2: “Mindless Evolution” Has All the Answers — If You Don’t Think About It Too Deeply

With more eye-popping CGI and new splendid scenes of Neil deGrasse Tyson touring the solar system in his high-tech spaceship, Cosmos Episode 2 weighed in Sunday night on some of life’s most profound questions. Toward the end of the episode, Tyson honestly admits, “Nobody knows how life got started,” and even says, “We’re not afraid to admit what we don’t know,” since “the only shame is to pretend we know all the answers.” By this late stage of the episode, however, that came off as a nervously inserted qualification since the rest of the episode had so vigorously argued that what Tyson calls the “transforming power” of “mindless evolution” or “unguided evolution” indeed has all the answers to how life evolved on Earth. Except, that is, for a few cases where evolution was guided by human breeders, through “artificial selection.”

Cosmos Episode 2 structures its argument much as Charles Darwin did in the Origin of Species. The opening scenes discuss how human breeders artificially selected many different dog breeds from wolf-like ancestors, including many popular breeds that “were created in only the last few centuries.” The argument is simple — and it’s the same type of argument that Darwin made: “If artificial selection can work such profound changes in only 10 or 15 thousand years, what can natural selection do operating over billions of years?” The answer, Tyson tells us, is “all the beauty and diversity of life.” In other words, Tyson wants you to believe that natural selection provides all the answers for everything since life arose. Just as he did in Episode 1, Tyson has overstated his case. The great evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr explains precisely why Tyson is wrong:

Some enthusiasts have claimed that natural selection can do anything. This is not true. Even though “natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinizing, throughout the world, every variation even the slightest,” as Darwin (1859:84) has stated, it is nevertheless evident that there are definite limits to the effectiveness of selection.1

Aside from the fact that artificial selection involves intelligent agents rather than unguided processes, Mayr makes one of the most important points in the context of artificial selection of dogs, for human breeders consistently hit limits in just how far they can breed dogs. The textbook Explore Evolution: The Arguments For and Against Neo-Darwinism explains:

Intense programs of breeding (and inbreeding) frequently increase the organism’s susceptibility to disease, and often concentrate defective traits. Breeders working with English bulldogs have strived to produce dogs with large heads. They have succeeded. These bulldogs now have such enormous heads that puppies sometimes have to be delivered by Cesarean section. Newfoundlands and Great Danes are both bred for large size. They now have bodies too large for their hearts and can suddenly drop dead from cardiac arrest. Many Great Danes develop bone cancer, as well. Breeders have tried to maximize the sloping appearance of a German Shepherd’s hind legs. As a result, many German Shepherds develop hip dysplasia, a crippling condition that makes it hard for them to walk. When breeders try to force a species beyond its limits, they often create more defects than desirable traits. These defects impose limits on the amount of change that breeders can ultimately produce.

Darwin’s theory states that the unguided force of natural selection is supposed to be able to do what the intelligent breeder can do. But even a process of careful, intentional selection encounters limits that neither time nor the efforts of human breeders can overcome. Consequently, critics argue that by the logic of Darwin’s own analogy, the power of natural selection is also limited.

Darwin’s theory requires that species exhibit a tremendous elasticity — or capacity to change. Critics point out that this is not what the evidence from breeding experiments shows.2

These aren’t just talking points from Darwin-critics. The same is heard from leading evolutionary biologists who say inconvenient things that Cosmos was content to ignore:

The following are three major areas of misconception among the Neo-Darwinists… Artificial selection on quantitative traits was taken as a model of the evolutionary process. It was easily shown, in agriculture or in the laboratory, that populations of most organisms contain sufficient additive genetic variance to obtain a response to selection on quantitative traits, such as measures of body size or increased yield of agriculturally valuable products such as milk in dairy cattle or grain size in food plants. Generalizing from this experience, it was assumed that natural populations are endowed with essentially unlimited additive genetic variance, implying that any sort of selection imposed by environmental changes will encounter abundant genetic variation on which to act. Moreover, this model was extended to evolutionary time as well as ecological time. This way of thinking ignored the substantial evidence from selection experiments that the response to selection on any trait essentially comes to a halt after a number of generations as the genetic variance for the trait in question is depleted; thereafter, further progress depends on the introduction of new variants either through outcrossing or new mutations (Falconer, 1981).3

Ernst Mayr concurs, citing “[t]he limited potential of the genotype” which shows “severe limits to further evolution”:

The existing genetic organization of an animal or plant sets severe limits to its further evolution. As Weismann expressed it, no bird can ever evolve into a mammal, nor a beetle into a butterfly. Amphibians have been unable to develop a lineage that is successful in salt water. We marvel at the fact that mammals have been able to develop flight (bats) and aquatic adaptation (whales and seals), but there are many other ecological niches that mammals have been unable to occupy. There are, for instance, severe limits on size, and no amount of selection has allowed mammals to become smaller than a pygmy shrew and the bumblebee bat, or allow flying birds to grow beyond a limiting weight.4

We cannot simply assert that evolution can do just “anything” or “all” we want it to — there are both genetic and physiological limits to how far breeders can change organisms. If we are to take artificial selection as an analogy for what can happen in the real world, shouldn’t this suggest there are also limits to evolution?

I’m sure Tyson would reply that we can overcome genetic barriers to further evolution through mutations, which provide new raw materials for evolution to act upon. According to Tyson, mutations “entirely random,” and can cause changes like transforming a bear’s fur color from brown to “white,” like “polar bears,” giving it a camouflage advantage in a snowy environment. (Technically, Cosmos got this small detail wrong, since the hairs of polar bears are transparent, not white.) “No breeder gathered these changes,” he tells us, since, “the environment itself selects them.”

Fair enough. While we might disagree with Tyson that natural selection is “the most revolutionary concept in the history of science,” no ID proponent denies that natural selection is an important idea that can explain many things. Changing the color of a bear’s coat from brown to white is probably one of them — it’s a small-scale, microevolutionary change. The difference between ID proponents and evolutionists like Tyson is that ID proponents acknowledge that natural selection is a real force in nature, but we don’t just unconditionally grant it the power to do all things. Instead, we test forces like natural selection, and find that there are limits to the amount of change it can effect in populations.

For example, after saying the “tree of life” (more on that shortly) is “three and a half billion years old,” Tyson just asserts that this provides “plenty of time” for the evolution of life’s vast complexity. Is this assertion true? We’ve heard that “plenty of time” claim before — in fact I recently rebutted that precise phrase and argument when Ken Miller made it in his textbook.

Tyson’s main argument that selection and mutation can evolve anything focuses on the evolution of the eye. Here, he attacks intelligent design by name, noting that some have argued that life “must be the work of an intelligent designer” that “created each of these species separately.” I’ve never heard of an ID proponent who requires that every single species was created separately, so that’s a straw man. Tyson calls the human eye a “masterpiece” of complexity, and claims it “poses no challenge to evolution by natural selection.” But do we really know this is true?

Darwinian evolution tends to work fine when one small change or mutation provides a selective advantage, or as Darwin put it, when an organ can evolve via “numerous, successive, slight modifications.” If a structure cannot evolve via “numerous, successive, slight modifications,” Darwin said, his theory “would absolutely break down.” Jerry Coyne essentially concurs: “It is indeed true that natural selection cannot build any feature in which intermediate steps do not confer a net benefit on the organism.”5 So are there structures that would require multiple steps to provide an advantage, where intermediate steps might not confer a net benefit on the organism? If you listen to Tyson’s argument carefully, I think he let slip that there are.

In his account of the evolution of the eye, Tyson says that “a microscopic copying error” gave a protein the ability to be sensitive to light. He doesn’t explain how that happened. Indeed, Sean B. Carroll cautions us to “not be fooled” by the “simple construction and appearance” of supposedly simple light-sensitive eyes, since they “are built with and use many of the ingredients used in fancier eyes.”6 Tyson doesn’t worry about explaining how any of those complex ingredients arose at the biochemical level. What’s more interesting is what Tyson says next: “Another mutation caused it [a bacterium with the light-sensitive protein] to flee intense light.”

This raises an interesting question: It’s nice to have a light-sensitive protein, but unless the sensitivity to light is linked to some behavioral response, then how would the sensitivity provide any advantage? Only once a behavioral response also evolved — say, to turn towards or away from the light — can the light-sensitive protein provide an advantage. So if a light-sensitive protein evolved, why did it persist until the behavioral response evolved as well? There’s no good answer to that question, because vision is fundamentally a multi-component, and thus a multi-mutation, feature. Multiple components — both visual apparatus and the encoded behavioral response — are necessary for vision to provide an advantage. It’s likely that these components would require many mutations. Thus, we have a trait where an intermediate stage — say, a light-sensitive protein all by itself — would not confer a net advantage on the organism. This is where Darwinian evolution tends to get stuck.

Indeed, ID research is finding that there are many traits that require many mutations before providing an advantage. For starters, protein scientist Douglas Axe has published mutational sensitivity tests on enzymes in the Journal of Molecular Biology and found that functional protein sequences may be as rare as 1 in 1077.7 That extreme rarity makes it highly unlikely that chance mutations alone could find the rare amino acid sequences that yield functional proteins:

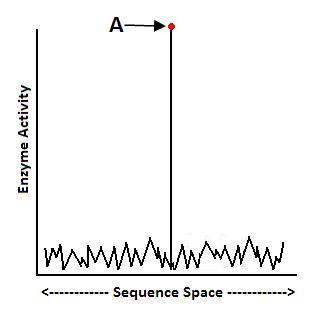

According to Axe’s research, most enzymes sit at Point A, high atop their fitness landscape, and many amino acids must be present all at once to get high enzyme functionality. This suggests that many mutations must be present in order to find the right sequences that yield stable protein folds, and thus functional enzymes.

I’m sure producers of Cosmos would reply that the “billions and billions” and of years of evolution provide “plenty of time” even for such unlikely events. But unless we test this claim, it’s a na�ve response. In 2010, Axe investigated how many mutations could arise in a multimutation feature given the entire history of the earth. He published population genetics calculations indicating that even when we grant generous assumptions favoring a Darwinian process, molecular adaptations requiring more than six mutations before yielding any advantage would be extremely unlikely to arise in the 4.5 billion year history of the Earth.8

The following year, Axe published research with developmental biologist Ann Gauger describing the results of their experiments seeking to convert one bacterial enzyme into another closely related enzyme — one in the same gene family! That is the kind of conversion that evolutionists claim can easily happen. For this case they found that the conversion would require a minimum of at least seven simultaneous changes9, exceeding the six-mutation-limit that Axe had previously established as a boundary of what Darwinian evolution is likely to accomplish in bacteria. Because this conversion is thought to be relatively simple, it suggests that converting one similar type of protein into another by “mindless evolution” might be highly unlikely.

In other experiments led by Gauger and biologist Ralph Seelke of the University of Wisconsin, Superior, their research team broke a gene in the bacterium E. coli required for synthesizing the amino acid tryptophan. When the bacteria’s genome was broken in just one place, random mutations were capable of “fixing” the gene. But even when only two mutations were required to restore function, Darwinian evolution got stuck, apparently unable to restore full function.10 Again, “mindless evolution” couldn’t overcome the need to produce multi-mutation features — those that require multiple mutations before providing an advantage.

Theoretical research into population genetics corroborates these empirical findings. Michael Behe and David Snoke have performed computer simulations and theoretical calculations showing that the Darwinian evolution of a functional bond between two proteins would be highly unlikely to occur in populations of multicellular organisms under reasonable evolutionary timescales when it required multiple mutations before functioning. They published research in Protein Science that found:

The fact that very large population sizes — 109 or greater — are required to build even a minimal MR feature requiring two nucleotide alterations within 108 generations by the processes described in our model, and that enormous population sizes are required for more complex features or shorter times, seems to indicate that the mechanism of gene duplication and point mutation alone would be ineffective, at least for multicellular diploid species, because few multicellular species reach the required population sizes.11

In other words, in multicellular species, Darwinian evolution would be unlikely to produce features requiring more than just two mutations before providing any advantage on any reasonable timescale or population size.

In 2008, Behe’s critics sought to refute him in the journal Genetics with a paper titled “Waiting for Two Mutations: With Applications to Regulatory Sequence Evolution and the Limits of Darwinian Evolution.” But Durrett and Schmidt found that to obtain only two specific mutations via Darwinian evolution “for humans with a much smaller effective population size, this type of change would take > 100 million years.”

The critics admitted this was “very unlikely to occur on a reasonable timescale.”12

What does this all mean? For one thing, it means Cosmos is wrong to assert we know that there is “plenty of time” for the “mindless evolution” of complex structures to take place. Both theoretical and empirical research suggest there are very good reasons why producing many of the new proteins and enzymes entailed by eye-evolution, and probably many other evolutionary pathways, would require the generation of multi-mutation features that could not arise via “mindless evolution” in the 3.5 billion year history of life on Earth. For another, it means Cosmos is pretending to have all the answers about how life evolved, when in fact it doesn’t. And thus, as David Berlinski has pointed out, it means that evolutionary biologists are very far away from explaining the evolution of the eye.

Evolutionary Apologetics and the Tree of Life

The second episode of Cosmos showcased quite a lot of evolutionary apologetics. What do I mean by that? I mean attempts to persuade people of both evolutionary scientific views and larger materialistic evolutionary beliefs, not just by the force of the evidence, but by rhetoric and emotion, and especially by leaving out important contrary arguments and evidence. This episode focused its evolutionary apologetics on the tree of life.

Tyson states that we have an “understandable human need” to think that we’re special, and thus “a central premise of traditional belief is that we were created separately from the other animals.” If you believe that, then you should know that it’s Neil deGrasse Tyson’s intention to talk you out of that “traditional belief,” and he’s going to use beautiful animation to do it, while ignoring explanations like “common design” and otherwise misstating the evidence.

This episode shows a beautifully animated “tree of life,” saying “science reveals that all life on earth is one,” and that “accepting our kinship with other animals” is “solid science.” But it’s not enough for Tyson if you just accept those evolutionary scientific views. The main message here is that humans aren’t special, since we are just “one tiny branch among countless millions.”

In case you think there’s room for reasonable intellectual doubt, Tyson compares evolution to gravity, casting evolution as an undeniable “scientific fact.”

Perhaps common ancestry is a fact. But what is Tyson’s evidence for it? It’s this: similarities in DNA sequences between humans and other species. The episode portrays similar DNA sequences between humans and other species — butterflies, wolves, mushrooms, sharks, birds, trees, and even one-celled organisms — and says that because “we and other species are almost identical” in some core metabolic genes, “the DNA doesn’t lie” and we are “long-lost cousins” with all these other organisms. With evolutionary apologetics in full force, Tyson even says this realization offers a “spiritual experience” — a nice bit of “woo,” included presumably to help appeal to the masses.

Spiritual or not, is it true that there’s a grand “tree of life” showing how we’re related to all other organisms?

A 2009 article in New Scientist concluded that the tree of life “lies in tatters, torn to pieces by an onslaught of negative evidence.”13 Why? Because one gene yields one version of the tree of life, while another gene gives another sharply conflicting version of the tree. The article explained what’s going on in this field:

For a long time the holy grail was to build a tree of life,” says Eric Bapteste, an evolutionary biologist at the Pierre and Marie Curie University in Paris, France. A few years ago it looked as though the grail was within reach. But today the project lies in tatters, torn to pieces by an onslaught of negative evidence. Many biologists now argue that the tree concept is obsolete and needs to be discarded.

“We have no evidence at all that the tree of life is a reality,” says Bapteste. That bombshell has even persuaded some that our fundamental view of biology needs to change.”

According to the article:

The problems began in the early 1990s when it became possible to sequence actual bacterial and archaeal genes rather than just RNA. Everybody expected these DNA sequences to confirm the RNA tree, and sometimes they did but, crucially, sometimes they did not. RNA, for example, might suggest that species A was more closely related to species B than species C, but a tree made from DNA would suggest the reverse.

The problem is rampant in systematics today. An article in Nature reported that “disparities between molecular and morphological trees” lead to “evolution wars” because “[e]volutionary trees constructed by studying biological molecules often don’t resemble those drawn up from morphology.”14 Another Nature paper reported that newly discovered genes “are tearing apart traditional ideas about the animal family tree” since they “give a totally different tree from what everyone else wants.”15 So severe are the problems that a 2013 paper in Trends in Genetics reported “the more we learn about genomes the less tree-like we find their evolutionary history to be,”16 and a 2012 paper in Annual Review of Genetics proposed “life might indeed have multiple origins.”17

Don’t expect Neil deGrasse Tyson and Cosmos to disclose to viewers that there are problems with reconstructing a grand “tree of life.” They need to maintain the pretense that “mindless evolution” provides all the answers — complete with a “spiritual experience” — even while disclaiming the fact that they’re making such a brash claim.

If not by “mindless” or “unguided” evolution and common ancestry, how can we explain the fact that genes in different organisms are so similar? Though Neil deGrasse Tyson never mentions it, a fully viable explanation or these functional genetic similarities is common design.

Intelligent agents often re-use functional components in different designs, which means common design is an equally good explanation for the very data — similar functional genes across different species — that Tyson cites in favor of common ancestry. As Paul Nelson and Jonathan Wells explain:

An intelligent cause may reuse or redeploy the same module in different systems, without there necessarily being any material or physical connection between those systems. Even more simply, intelligent causes can generate identical patterns independently.18

Likewise, in their book Intelligent Design Uncensored, William Dembski and Jonathan Witt explain:

According to this argument, the Darwinian principle of common ancestry predicts such common features, vindicating the theory of evolution. One problem with this line of argument is that people recognized common features long before Darwin, and they attributed them to common design. Just as we find certain features cropping up again and again in the realm of human technology (e.g., wheels and axles on wagons, buggies and cars) so too we can expect an intelligent designer to reuse good design ideas in a variety of situations where they work.19

Thus, common design is a possible explanation for why two taxa can have highly similar functional genetic sequences. After all, designers regularly re-use parts, programs, or components that work in different designs. As another example, engineers use wheels on both cars and airplanes, or technology designers put keyboards on both computers and cell-phones. Or software designers re-use subroutines in different software programs.

But common designers aren’t always obligated to design their designs according to a nested hierarchy. So when we find re-use of functional components in a pattern that doesn’t match a nested hierarchy, we might look to common design. But wait — that’s exactly what we have here: similar genes being re-used in different organisms, but in a pattern that doesn’t match the “tree-like” distribution predicted by Darwinian theory! Unfortunately, Neil deGrasse Tyson doesn’t inform his viewers of any of this.

The Evidence for Design Speaks for Itself

In this second episode of Cosmos, Neil deGrasse Tyson and his co-creators hoped to convince viewers that intelligent design is wrong, but discussing by simply the complexity of biology, they couldn’t help but expose people to the evidence for design in nature. When Cosmos Episode 2 showed brilliant animations of walking kinesin motors, and discussed the fact that DNA is a “molecular machine” that is “written in a language that all life can read,” it unwittingly showed that intelligent design is a viable explanation. After all, what is the sole known cause that produces languages and machines? That one singular cause is, of course, intelligence. Even when you try to disregard the evidence for design in nature, it nevertheless speaks for itself.

[Update, 3/18/14: In a rebuttal filled with ad hominem attacks, journalist Chris Mooney attempts to respond to this article by claiming that “science deniers” are “freaking out” over Cosmos. His one substantive rebuttal is that the “tree of life” is doing just fine because of the “Open Tree of Life project, which plans to produce ‘the first online, comprehensive first-draft tree of all 1.8 million named species, accessible to both the public and scientific communities.'” I’m sure that’s a worthwhile project, but Mooney’s comments don’t address the fact a “treelike pattern” is fundamentally incompatible with much of the data being discovered by molecular biology.

The condundrum folks working with the Open Tree of Life project will face is this: Which tree is the real tree of life? They’ll find that one gene gives you one version of the tree of life, and another gene gives an entire different, conflicting version of the tree of life. This is because the genetic data is not painting a consistent picture of common ancestry. Mooney wants his readers to think these are isolated problems, since the attempt to “reconstruct every last evolutionary relationship may still be an open scientific question, but the idea of common ancestry, the core of evolution (represented conceptually by a tree of life), is not.” Actually, conflicts in the tree of life are rampant. As a 2012 paper in stated, “Phylogenetic conflict is common, and frequently the norm rather than the exception,” and “Phylogenetic conflict has become a more acute problem with the advent of genomescale data sets.”20 Or, as Michael Syvanen stated for the New Scientist article quoted above, “We’ve just annihilated the tree of life. It’s not a tree any more, it’s a different topology entirely.” That seems to suggest scientists contributing to the “Open Tree of Life project” may have be in for far greater difficulties than Mooney is letting on. In short, Mooney hasn’t addressed the criticisms I raised.

Had Mooney provided a non-ad-hominem-filled, evidence-based rebuttal that addressed my points, then I suppose I might have be wondering if my views are wrong. But given that he’s resorting to so much namecalling and has not engaged our arguments, far from “freaking out,” I’m actually quite encouraged.]

References Cited:

[1.] Ernst Mayr, What Evolution Is, pg. 140 (Basic Books, 2001).

[2.] Stephen C. Meyer, Scott Minnich, Jonathan Moneymaker, Paul A. Nelson, and Ralph Seelke, Explore Evolution: The Arguments For and Against Neo-Darwinism, p. 91 (Hill House, 2007).

[3.] Austin L. Hughes, “Looking for Darwin in all the wrong places: the misguided quest for positive selection at the nucleotide sequence level,” Heredity, 99: 364-373 (2007).)

[4.] Ernst Mayr, What Evolution Is, p. 140 (Basic Books, 2001).

[5.] Jerry Coyne, “The Great Mutator,” The New Republic (June 14, 2007).

[6.] Sean B. Carroll, The Making of the Fittest: DNA and the Ultimate Forensic Record of Evolution, p. 197 (W.W. Norton, 2006).

[7.] Douglas Axe, “Estimating the Prevalence of Protein Sequences Adopting Functional Enzyme Folds,” Journal of Molecular Biology, 341 (2004): 1295-1315; Douglas Axe, “Extreme Functional Sensitivity to Conservative Amino Acid Changes on Enzyme Exteriors,” Journal of Molecular Biology, 301 (2000): 585-595.

[8.] Douglas Axe, “The Limits of Complex Adaptation: An Analysis Based on a Simple Model of Structured Bacterial Populations,” BIO-Complexity, 2010(4):1-10.

[9.] Ann Gauger and Douglas Axe, “The Evolutionary Accessibility of New Enzyme Functions: A Case Study from the Biotin Pathway,” BIO-Complexity, 2011 (1): 1-17.

[10.] Ann Gauger, Stephanie Ebnet, Pamela F. Fahey, and Ralph Seelke, “Reductive Evolution Can Prevent Populations from Taking Simple Adaptive Paths to High Fitness,” BIO-Complexity, 2010 (2): 1-9.

[11.] Michael Behe and David Snoke, “Simulating Evolution by Gene Duplication of Protein Features that Require Multiple Amino Acid Residues,” Protein Science, 13 (2004): 2651-2664.

[12.] Rick Durrett and Deena Schmidt, “Waiting for Two Mutations: With Applications to Regulatory Sequence Evolution and the Limits of Darwinian Evolution,” Genetics, 180 (November 2008): 1501-1509.

[13.] Graham Lawton, “Why Darwin was wrong about the tree of life,” New Scientist (January 21, 2009).

[14.] Trisha Gura, “Bones, Molecules or Both?,” Nature, 406 (July 20, 2000): 230-233.

[15.] Elie Dolgin, “Rewriting Evolution,” Nature, 486 (June 28, 2012): 460-462.

[16.] Bapteste et al., “Networks: expanding evolutionary thinking,” Trends in Genetics, 29 (2013): 439-41.

[17.] Michael Syvanen, “Evolutionary Implications of Horizontal Gene Transfer,” Annual Review of Genetics, 46 (2012): 339-56.

[18.] Paul Nelson and Jonathan Wells, “Homology in Biology,” in Darwinism, Design, and Public Education, p. 316 (Michigan State University Press, 2003).

[19.] William Dembski and Jonathan Witt, Intelligent Design Uncensored: An Easy-to-Understand Guide to the Controversy, p. 85 (InterVarsity Press, 2010).

[20.] Liliana M. D�valos, Andrea L. Cirranello, Jonathan H. Geisler, and Nancy B. Simmons, “Understanding Phylogenetic Incongruence: Lessons from Phyllostomid Bats,” Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 87 (2012): 991-1024.