Physics, Earth & Space

Physics, Earth & Space

Big Bang Exterminator Wanted, Will Train

What help has materialism been in understanding the universe’s beginnings?

Many in cosmology have never made any secret of their dislike of the Big Bang, the generally accepted start to our universe first suggested by Belgian priest Georges Lema�tre (1894-1966).

On the face of it, that is odd. The theory accounts well enough for the evidence. Nothing ever completely accounts for all the evidence, of course, because evidence is always changing a bit. But the Big Bang has enabled accurate prediction.

On the face of it, that is odd. The theory accounts well enough for the evidence. Nothing ever completely accounts for all the evidence, of course, because evidence is always changing a bit. But the Big Bang has enabled accurate prediction.

In which case, its hostile reception might surprise you. British astronomer Fred Hoyle (1915-2001) gave the theory its name in one of his papers — as a joke. Another noted astronomer, Arthur Eddington (1882-1944), exclaimed in 1933, “I feel almost an indignation that anyone should believe in it — except myself.” Why? Because “The beginning seems to present insuperable difficulties unless we agree to look on it as frankly supernatural.”

One team of astrophysicists (1973) opined that it “involves a certain metaphysical aspect which may be either appealing or revolting.” Robert Jastrow (1925-2008), head of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, initially remarked, “On both scientific and philosophical grounds, the concept of an eternal Universe seems more acceptable than the concept of a transient Universe that springs into being suddenly, and then fades slowly into darkness.” And Templeton Prize winner (2011) Martin Rees recalls his mentor Dennis Sciama’s dogged commitment to an eternal universe, no-Big Bang model:

For him, as for its inventors, it had a deep philosophical appeal — the universe existed, from everlasting to everlasting, in a uniquely self-consistent state. When conflicting evidence emerged, Sciama therefore sought a loophole (even an unlikely seeming one) rather as a defense lawyer clutches at any argument to rebut the prosecution case.

Evidence forced theorists to abandon their preferred eternal-universe model. From the mid 1940s, Hoyle attempted to disprove the theory he named. Until 1964, when his preferred theory, the Steady State, lost an evidence test.

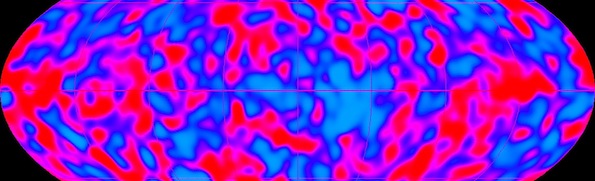

In 1965, an unexpected discovery both confirmed and publicized the Big Bang: Two physicists at AT&T Bell Laboratories in New Jersey, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, accidentally discovered the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the radiation apparently left over from the origin. Then in 1990, NASA’s Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) satellite confirmed Big Bang cosmology with more accurate measurements. A 2011 discovery of gas generated minutes after the Big Bang further confirmed predictions.

That wasn’t good news for those who track the progress of science by the progress of atheism. “These men and women have built their entire worldview on atheism,” says cosmologist Frank Tipler: “When I was a student at MIT in the late 1960s, I audited a course in cosmology from the physics Nobelist Steven Weinberg. He told his class that of the theories of cosmology, he preferred the Steady State Theory because ‘it least resembled the account in Genesis.'”

So disapproval snowballed along with evidence rather than with disconfirmation. In 1989, Nature‘s physics editor John Maddox predicted, “Apart from being philosophically unacceptable, the Big Bang is an over-simple view of how the Universe began, and it is unlikely to survive the decade ahead.” In 1992, Geoffrey Burbidge of the University of California at San Diego taxed his colleagues with rushing off to join “the First Church of Christ of the Big Bang.” Stephen Hawking opined in 1996, “Many people do not like the idea that time has a beginning, probably because it smacks of divine intervention. … There were therefore a number of attempts to avoid the conclusion that there had been a big bang.”

Hawking himself offered one such attempt: He tried designing a design-free universe. To make his cosmology work, he relied on imaginary time rather than real time, explaining, “Maybe what we call imaginary time is really more basic, and what we call real is just an idea that we invent to help us describe what we think the universe is like.”

Cute inversion of imaginary vs. real. The problem is that one must convert one’s results back to real time to say anything meaningful about the real world.

Another alternative was an oscillating universe that swings back and forth, into and out of existence. Quantum cosmologist Christopher Isham recalls,

Perhaps the best argument in favor of the thesis that the Big Bang supports theism is the obvious unease with which it is greeted by some atheist physicists. At times this has led to scientific ideas, such as continuous creation or an oscillating universe, being advanced with a tenacity which so exceeds their intrinsic worth that one can only suspect the operation of psychological forces lying very much deeper than the usual academic desire of a theorist to support his/her theory.

In any event, the Maddox obituary (“unlikely to survive the next decade”) was certainly premature. Though disliked, the Big Bang has accounted well enough for the evidence that it can’t just be dismissed, exploded, or destroyed.

The Big Bang stubbornly refused to provide obvious support for materialism. Worse, things got worse. Not only, on the evidence, does the universe look like it was suddenly created, it also looks finely tuned. New Scientist‘s Marcus Chown notes:

… it seems as if the strength of any of the fundamental forces or masses of the fundamental particles were different by even a small amount, they would not have created a universe with galaxies, stars, planets and life.

Or as cosmologist Max Tegmark explains:

If the cosmological constant were much larger, the universe would have blown itself apart before galaxies could form.

A reasonable explanation would be design in nature. But materialism operates on the principle that reason and the human mind are an illusion. So that explanation can’t be true, by definition. There has to be a more acceptable alternative. As we shall see, it is remarkable what people determined to explain something away will see as an acceptable alternative.

Image: Cosmic Microwave Background/Wikipedia.