Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Rush to Judgment: Nick Matzke’s Hasty Review of Darwin’s Doubt Makes Bogus Charges of Errors and Ignorance

There’s an old joke about a book critic. Asked if he has read the new book by a certain author, he replies, “No, I only had time to review it.”

On Wednesday, June 19, the day after Stephen C. Meyer’s book Darwin’s Doubt: The Explosive Origin of Animal Life and the Case for Intelligent Design was published and made available for purchase, UC Berkeley grad student Nick Matzke posted a harsh 9400+ word review on the blog Panda’s Thumb.

Since then, University of Chicago evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne, perhaps the most prominent American advocate of neo-Darwinism, has touted the review as a supposedly “excellent” critique. Because of Coyne’s prominence, and his endorsement of Matzke’s review, it’s worth evaluating a few of Matzke’s claims.

Now, Darwin’s Doubt runs to 413 pages, excluding endnotes and bibliography. Neither the book’s publisher, HarperOne, nor its author sent Matzke a prepublication review copy. Did Matzke in fact read its 400+ pages and then write his 9400+ word response — roughly 30 double-spaced pages — in little more than a day?

Perhaps, but a more likely hypothesis is that he wrote the lion’s share of the review before the book was released based upon what he presumed it would say. A reviewer who did receive a prepublication copy, University of Pittsburgh physicist David Snoke, writes:

A caution: this is a tome that took me two weeks to go through in evening reading, and I am familiar with the field. Like the classic tome G�del, Escher, Bach, it simply can’t be gone through quickly. I was struck that the week it was released, within one day of shipping, there were already hostile reviews up on Amazon. Simply impossible that they could have read this book in one night.

Even if Snoke is wrong, and Matzke possesses a preternatural capacity to read and write at blinding speed, Matzke in his haste has made some significant errors — of commission and omission — in his representation and assessment of Meyer’s work.

Matzke misrepresents what Meyer actually says, going so far as to attribute quotes and arguments to him that nowhere appear in the book. He also fails to address, let alone to refute, Meyer’s central arguments. Instead, he attempts to impugn Meyer’s credibility by asserting that Meyer makes various minor factual errors, which turn out not to be errors at all. Most unfortunately, Matzke gets personal, asserting that these alleged mistakes show that Meyer is ignorant, lazy, arrogant and even dishonest. Matzke writes:

Here it is completely clear that the creationists/IDists are arrogant enough to call God down from Heaven to cover for their ignorance, basically because they are unwilling to do the basic “due diligence” and hard work required to get a basic understanding of the topic they [sic] commenting on. I’m not sure that most long-lived religious traditions actually support that kind of behavior.

And so Matzke attempts to convince readers that they should distrust the man, Stephen Meyer, and ultimately disregard the book that he has authored, a strategy that Matzke and his colleagues at the National Center for Science Education have repeatedly used to suppress interest in and consideration of the evidence for intelligent design. Thus, the punch line of Matzke’s review (emphasis added):

I’m not sure it [Darwin’s Doubt] deserves much more of anyone’s time.

Since I think it would be a shame for readers to miss out on what Meyer has actually written, and since Matzke and other early reviewers on Amazon grossly misrepresent Meyer’s argument, I want to set the record straight.

Meyer’s Critique of Neo-Darwinism

In Darwin’s Doubt, Meyer argues that the Cambrian explosion presents two separate challenges to contemporary neo-Darwinian evolutionary theory — the first of which Darwin himself also acknowledged in 1859 as a problem for his original theory of evolution. First, Meyer argues that the geologically sudden appearance of many novel forms of animal life in the Cambrian period, and the absence of fossilized ancestral precursors for most of these animals in lower Precambrian strata, challenges the gradualistic picture of evolution envisioned by both Darwin and modern neo-Darwinian scientists — a problem that many paleontologists have long acknowledged.

Second, and more importantly, Meyer argues that the neo-Darwinian mechanism lacks the creative power to produce the new animal forms that first appear in the Cambrian period, a view that many evolutionary biologists themselves now share. Meyer, in particular, argues that the mutation and natural selection mechanism lacks the creative power to produce both the genetic and epigenetic information necessary to build the animals that arise in Cambrian. Meyer offers five separate lines of evidence and arguments to support this latter claim. He also later describes and critiques six post neo-Darwinian evolutionary theories and makes a positive argument for intelligent design as well.

Matzke does attempt to address the first problem posed by the Cambrian explosion. He does so by claiming that methods of phylogenetic reconstruction can establish the existence of Precambrian ancestral and intermediate forms — an unfolding of animal complexity that the fossil record does not document. Though he accuses Meyer of being ignorant of these phylogenetic methods and studies, he seems unaware that Meyer explains and critiques attempts to reconstruct phylogenetic trees based upon the comparisons of anatomical and genetic characters in his fifth and sixth chapters. He also criticizes Meyer for being ignorant of cladistics in reconstructing such phylogenetic trees, though, again, Meyer critiques many of the assumptions and methods of cladistics in the context of the larger evaluation of phylogenetic reconstruction that he (Meyer) offers in those chapters (as well as in accompanying endnotes, as I’ll explain).

One could say more in response to Matzke’s substantive claims about phylogenetic analysis. For now, I recommend Meyer’s book itself, specifically his chapters titled “The Genes Tell the Story?” and “The Animal Tree of Life” for any interested reader wanting to know about the problems (that Matzke does not report) with reconstructing phylogenetic trees using these methods. Though Matzke gives the impression of having dealt with these chapters in his review, he doesn’t.

Indeed, Matzke scarcely addresses Meyer’s second and more central critique of neo-Darwinism. Matzke does not respond in any detail to any of Meyer’s multiple challenges to the creative power of the mutation/selection mechanism.

He does not attempt to show that the neo-Darwinian mechanism can efficiently search combinatorial sequence space or attempt to refute empirical studies showing that functional genes and proteins are exceedingly rare within such spaces (contra Meyer’s first argument).

Nor does he show that the mechanism can generate multiple coordinated mutations within realistic waiting times (contra Meyer’s second critique) — except to reassure us without justification that the need for such mutations is exceedingly rare.

Nor does he explain (contra Meyer’s third argument) how the neo-Darwinian mechanism could ever produce new body plans given that mutagenesis experiments show how early acting body plan mutations — the very mutations that would be necessary to produce whole new animals from a pre-existing animal body plan — inevitably produce embryonic lethals.

He does not address Meyer’s fourth critique of the neo-Darwinian mechanism by explaining how mutations could alter development gene regulatory networks to produce new developmental regulatory networks, though the production of such a new regulatory network is an important requirement for building any new animal body plan from a pre-existing body plan.

Finally, Matzke does not explain how mutations in DNA alone could produce the epigenetic (“beyond the gene”) information necessary to build new animal body plans, a problem that has led many evolutionary biologists to seek a new theory of and mechanism for major evolutionary innovation.

Of course, he also fails to show how any of the “post-Darwinian” models critiqued by Meyer could have produced the requisite information for generating animal complexity.

Meyer offers five detailed scientific critiques of the alleged creative power of the mutation/selection mechanism. Yet Matzke in his nearly 10,000-word review offers no detailed response to any. Since Matzke does not address the central critical arguments of Meyer’s book, he has not refuted them or shown, therefore, that Darwin’s Doubt lacks scientific merit.

So what does Matzke do in his review?

Apart from arguing that phylogenetic analysis circumvents the problem of missing ancestral fossils, Matzke mainly attempts to impeach Meyer’s credibility by pointing to minor, alleged factual errors — errors that, even if Meyer had committed them, would not matter to the substance of the book. Nevertheless, even here Matzke’s review fails because Meyer either does not make the errors that Matzke claims, or the “errors” he alleges are not in fact errors.

Nickpicking at “Errors” That Are Not Errors

Matzke claims that Meyer makes two clear-cut “errors” in Darwin’s Doubt pertaining to proper schemes of taxonomic classification. He alleges, first, that Meyer blunders by calling Anomalocaris (literally “abnormal shrimp”) an “arthropod.” And he claims, second, that Meyer incorrectly calls lobopodia a phylum.

In his Amazon review, Matzke writes:

He makes basic errors like calling Anomalocaris an arthropod and calling lobopods a “phylum,” not noting for the readers that Anomalocaris falls well outside of the crown arthropod phylum, far down in the lobopods, and that the phylum Arthropoda is thought to have evolved from lobopods, as did one or two other phyla. The lobopods are a paraphyletic assemblage of stem taxa, i.e. the very “transitional forms” between phyla that Stephen Meyer claims to be looking for! This is Cambrian Explosion 101 stuff that Meyer gets wrong.

Matzke says much the same on Panda’s Thumb:

Meyer continually and blithely refers to organisms such as Anomalocaris as “arthropods,” as if this were an obvious and uncontroversial thing to say. But in fact, anyone actually mildly familiar with modern cladistic work on arthropods and their relatives would realize that Anomalocaris falls many branches and many character steps below the arthropod crown group (see the figure above). Anomalocaris lacks many of the features found in arthropods living today. It is one of many fossils with transitional morphology between the crown-group arthropod phylum, and the next closest living crown group, Onychophora (velvet worms).

Notably, these supposed errors pertain to classification, which is a highly subjective science. There are strong differences of opinion and much debate about many points regarding the proper classification of Cambrian animals. In fact, Matzke effectively concedes this point in his review, as he calls the definition of phyla “arbitrary and flexible,” thus undercutting his own accusations. What Matzke calls “basic errors” really just reflect differences of opinion among experts about how to best classify different Cambrian animals. Even so, Stephen Meyer cites prominent authorities in support of his judgments and positions on classification. Yet in criticizing Meyer, Matzke chooses to ignore that supporting technical literature. Oddly, Matzke also offers no page numbers for his claim that Meyer calls Anomalocaris an arthropod, but I’m happy to fill readers in about what Meyer actually wrote. Meyer addresses this topic on pages 53 and 60 of Darwin’s Doubt, writing:

“Anomalocaris (literally, “abnormal shrimp”) and Marrella. . . had hard exoskeletons and clearly represent either arthropods or creatures closely related to them. Yet each of these animals possessed many distinct anatomical parts and exemplified different ways of organizing these parts, thus clearly distinguishing themselves from better-known arthropods such as the previous staple of Cambrian paleontological studies, the trilobite.” (p. 53)

“There are many types of arthropods that arise suddenly in the Cambrian — trilobites, Marrella, Fuxianhuia protensa, Waptia, Anomalocaris — and all of these animals had hard exoskeletons or body parts.” (p. 60)

Matzke neither quotes nor cites either of these passages, and neither supports his criticism.

In the first quote, from page 53, we see that Meyer called Anomalocaris “either arthropods or creatures closely related to them,” showing his awareness that there is ambiguity and debate over whether Anomalocaris belongs directly within arthropods, or was a close relative. Matzke never quotes Meyer’s statement on this point, which is consistent both with what Matzke says about anomalocaridids, and with the relevant scientific literature. Instead, Matzke seems unfamiliar with what Meyer actually wrote.

In the second quote, from page 60, Meyer suggests that Anomalocaris may in fact be an arthropod. Would it be a “basic error” to make that claim? Not at all, because many leading authorities on the Cambrian explosion have suggested precisely the same thing –that Anomalocaris is an arthropod.

One authoritative source on this point is a 2011 Nature paper about anomalocaridids by Paterson et al., titled “Acute vision in the giant Cambrian predator Anomalocaris and the origin of compound eyes,” which concluded:

These fossils also provide compelling evidence for the arthropod affinities of anomalocaridids, [and] push the origin of compound eyes deeper down the arthropod stem lineage.

The paper firmly places anomalocaridids as stem-group arthropods, very close to the crown-group arthropods, and has some weighty co-authors, including John R. Paterson of the University of New England in Australia, Diego C. García-Bellido of the Instituto de Geociencias in Spain, Michael S. Y. Lee of South Australian Museum and the University of Adelaide, Glenn A. Brock of Macquarie University, James B. Jago of the University of South Australia, and Gregory D. Edgecombe of the Natural History Museum in London. In covering this paper, Discover Magazine stated: “Paterson also argues that the eyes confirm that Anomalocaris was an early arthropod, for this is the only group with compound eyes.”

Likewise Benjamin Waggoner (then of UC Berkeley, now at the University of Central Arkansas) writes in the journal Systematic Biology that “the anomalocarids and their relatives (Anomalopoda) fall out very close to the base of the traditional Arthropoda and should be included within it.” A 2006 paper in the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica likewise refers to the “anomalocaridid arthropods.” The authoritative book The Cambrian Fossils of Chengjiang China states that anomalocaridid “morphology recalls features of several phyla, including worm groups, lobopodians, and arthropods. They have been regarded as related to one of these groups, or as arthropods, or as forming an unrelated group.” (p. 94) The leading authorities Charles R. Marshall and James W. Valentine note in a 2010 article in the journal Evolution, titled “The importance of preadapted genomes in the origin of the animal bodyplans and the Cambrian explosion,” that “Anomalocaris most likely lies in the diagnosable stem group of the Euarthropoda (but in the crown group of Panarthropoda).” Writing in Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, Graham Budd and S�ren Jensen call Anomalocaris, along with Opabinia, “stem group arthropods.” In the journal Integrative & Comparative Biology, Nicholas Butterfield of the University of Cambridge calls Anomalocaris an “arthropod”:

A number of arthropods, however, also feature conspicuously three-dimensional phosphatized gut structures, most notably Leanchoilia (Fig. 4), Odaraia, Canadaspis, Perspicaris, Sydneyia, Anomalocaris and Opabinia.

Meyer doesn’t try to enter into the debate over whether Anomalocaris is a “stem group” or “crown group” arthropod, or a member of Euarthropoda, or Panarthropoda. But in calling it an “arthropod” of some type, Meyer can cite many, many scientific authorities who agree with his judgment. Since Meyer states that anomalocaridids are “either arthropods or creatures closely related to them,” and that they “possessed many distinct anatomical parts and exemplified different ways of organizing these parts, thus clearly distinguishing themselves from better-known arthropods,” his position is smack dab in the middle of the consensus view.

But, of course Matzke doesn’t accuse Nature, Budd, Jensen, or the authors of any of these other papers of committing a “basic error” for calling Anomalocaris an “arthropod.” In fact, it seems that Matzke is the one who made the “basic error” in not reading Meyer carefully, and/or not knowing what the literature says.

Now in checking out Matzke’s claim, we discovered that there is an actual error in Darwin’s Doubt regarding Anomalocaris, though it isn’t anything that Matzke caught. On page 53 Meyer says that Anomalocaris has an exoskeleton — when it would have been more accurate to state things as he did on page 60, where he said it “had hard exoskeletons or body parts.” The jaw of Anomalocaris is commonly preserved as a fossil, probably because it is a hard part, which was used to hunt hard-shelled organisms. So Anomalocaris probably did have “hard parts,” but it did not have an exoskeleton. Meyer will correct the oversight in a future edition and note it on his website.

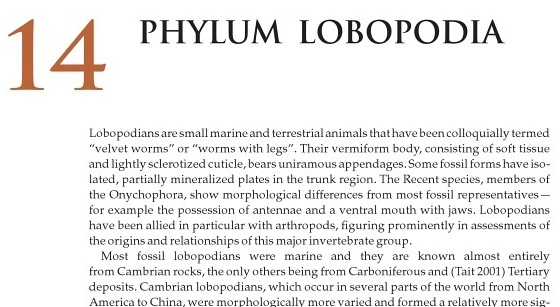

And what about Matzke’s other accusation of an alleged error — his claim that Lobopodia isn’t a phylum? Again, we’re talking about questions of classification here, where there have been many disagreements among scientists about just what is, or isn’t, a phylum. Recall that Matzke himself called phyla “arbitrary and flexible.” True, there are paleontologists who don’t consider Lobopodia a phylum. Some call it a “superphylum,” others just a “taxon”; some say it’s paraphyletic and others that it is monophyletic. But there are weighty authorities that do consider Lobopodia a phylum.

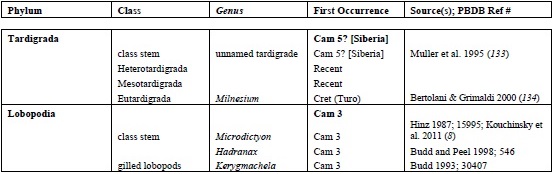

For example, Lobopodia has been called a “phylum” by one of the leading Cambrian paleontologists, Douglas Erwin, and his co-authors on a 2011 paper in Science, “The Cambrian Conundrum: Early Divergence and Later Ecological Success in the Early History of Animals.” Their paper attempted an ambitious comprehensive survey of the first appearance of all of the animal phyla in the fossil record, and in the supplemental data, they list “Lobopodia” as a “phylum” that first appears in the Cambrian. Here’s a screenshot of that entry in Table S1 of their supplemental data, pasted with the column titles shown directly above:

Note the entry for phylum Tardigrada, showing that Meyer was justified in following Erwin et al. by listing the two groups as separate phyla, in contrast to Matzke’s charge of “huge mistakes” on this point. Note also that this same table is presented and endorsed by Douglas Erwin and James Valentine in their new book The Cambrian Explosion (p. 350).

Other authorities confirm the point about Lobopodia. In a paper in Biological Review of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, the eminent Thomas Cavalier-Smith has also classified Lobopodia as one of “three new phyla” in the animal kingdom. The respected biology website Palaeos.com likewise suggests it could be a phylum.

But perhaps the most authoritative source on this is the book The Cambrian Fossils of Chengjiang, China: The Flowering of Early Animal Life (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004). Here is what page 82 looks like:

This pretty much puts to rest any claims by Matzke that Meyer made some kind of a “basic error” by referring to phylum Lobopodia.

As a side note, Erwin et al.‘s 2011 paper (as well as some other leading authorities) also challenges Matzke’s claim that the Cambrian explosion lasted 30+ million years. Let it suffice to say that both of Matzke’s supposed examples of Meyer’s “basic errors” turn out to be bogus.

Again, even if Meyer had made errors in classifying one of the many Cambrian animals, that would in no way affect the strength of his overall argument. The Cambrian fossil record would pose the same two problems to neo-Darwinian theory that Meyer describes at length in his book. Instead, Matzke is simply nitpicking.

“Ignorance” That Isn’t Ignorance: Meyer’s Arguments and the Scientific Literature

Matzke claims that Meyer is ignorant of basic concepts in systematics and evolutionary classification, like “stem groups” and “crown groups.” He also implies that Meyer doesn’t understand why some systematists today reject attempts to classify organisms within traditional Linnean categories such as “phyla.” Nevertheless, Meyer provides ample discussion of topics like rank-free classification systems, as anyone who read the book carefully would know. Page 419 of Darwin’s Doubt has a very nice discussion of stem groups and crown groups, and on pages 31-33, 43, 55, and 418-419, Meyer writes about the concept of “rank-free classification,” currently fashionable among some systematists, as well as other phylogenetic concepts.

Meyer’s book isn’t intended to be a treatise on classification, so he doesn’t devote pages and pages to these controversial and hotly debated topics, but Meyer certainly devotes significant space to topics that Matzke claims that Meyer ignores (or doesn’t understand). And please note: This post is not intended to be a thorough substantive response to Matzke regarding phylogenetics; that will come later. As I noted earlier, Chapters 5 and 6 discuss many fundamental assumptions in phylogenetic methods and critiques them, demonstrating a familiarity with the methods and the literature. Matzke utterly fails to engage this discussion — the word “assumption” isn’t even in his review. Despite Matzke’s many words on phylogenetics, he never offers any evidence that Meyer is ignorant of these topics and concepts or their relevance to his discussion of the Cambrian explosion. Nonetheless, Matzke makes bizarre charges like this:

I think that if you plunked those fossils down in front of an ID advocate without any prior knowledge except the general notion of taxonomic ranks, the ID advocate would place most of them in a single family of invertebrates, despite the fact that phylogenetic classification puts some of them inside the arthropod phylum and some of them outside of it.

In another instance, Matzke enthusiastically mentions concepts in phylogenetic tree construction like long branch attraction, hoping they can resolve the many conflicts among phylogenetic trees. He criticizes Meyer for neglecting to consider these proposals. But Matzke seems unaware that Meyer has a lengthy 450+ word endnote on page 432 where he not only writes about long branch attraction, but addresses why that idea and many other ad hoc explanations fail to account for conflicts among phylogenetic trees. Though Matzke accuses Meyer of ignorance of these phylogenetic concepts and proposals, it rather appears that Matzke is ignorant of Meyer’s discussion of them.

Indeed, though Matzke accuses Meyer of ignorance and “basic errors” in his scientific scholarship, Matzke’s review betrays scant familiarity with the substance of Meyer’s book. Of the 9400+ words in the review, fewer than 150 words are actual quotations from Darwin’s Doubt. In fact, of the 30 or so apparent quotes in his post, all but four are three words or less. For example, Matzke seems to have presciently anticipated that Meyer would use terms such as “intelligent design,” “explosion,” “information,” “phylum,” and “fish.”

In fact, I find only four instances where Matzke quotes Meyer at a length of more than five words at a time, which together total about 116 words from the book. As I noted, in no case does Matzke provide a page number for any quote he attributes to Meyer. This leads to the next problem with Matzke’s review.

Matzke’s False Attributions

While I personally tend to suspect he didn’t, in the end it doesn’t matter whether Matzke read Darwin’s Doubt before writing the bulk of his review, or whether he wrote it before the book was out based on presuppositions and then glanced through the page once he had it in hand. Either way, his misrepresentations in matters large and small are inexcusable.

For example he attributes to Meyer in quotation marks quotes that nowhere appear in the book. Matzke claims Meyer used the phrases “ancestral phyla,” “multiple mutations required,” or “conflicts between trees” but I cannot find those phrases in the book. Some of these misquotes (like “multiple mutations required” or “conflicts between trees”) aren’t necessarily far off from things Meyer does say, but Matzke’s invention of quotations, like the bogus accusations of “errors,” impeaches his credibility as a reviewer of Meyer’s work.

But there are obvious examples of invented quotes, such as when he claims Meyer argues that “poof, God did it” — words he attributes to Meyer by putting them in quotation marks, though Meyer never argued or said such a thing. Matzke offers other descriptions of Meyer’s argument for design which bear no resemblance to Meyer’s extensive, rigorous explication of the positive case for design in Chapters 17 through 20. You’d never know it from reading Matzke’s review, but Meyer explains why the standard scientific methods of historical sciences and rigorous abductive logic establish intelligent design as the only known sufficient cause for generating the information and top-down design that are required to build the animal body plans which appear explosively in the Cambrian period.

To cite another example, Matzke claims that Meyer said the Cambrian explosion was “instantaneous.” Actually, the word “instantaneous” does appear in Darwin’s Doubt in two places — but neither is from prose originally written by Meyer, and neither is necessarily intended to specifically describe the Cambrian explosion. In fact, both uses of that word in the book are from quotes by Stephen Jay Gould. Here’s what Gould says:

“But the earth scorns our simplifications, and becomes much more interesting in its derision. The history of life is not a continuum of development, but a record punctuated by brief, sometimes geologically instantaneous, episodes of mass extinction and subsequent diversification.” (quoted on pp. 15-16)

“Most evolutionary change, we argued, is concentrated in rapid (often geologically instantaneous) events of speciation in small, peripherally isolated populations (the theory of allopatric speciation).” (quoted on p. 434)

Yet Matzke attributes the word “instantaneous” to Meyer, and calls Meyer “ignorant” because (in his view) “[t]he ‘body plans’ did not originate instantaneously.” But I can find nowhere in the book where Meyer uses the word “instantaneous” to describe the origin of body plans. Needless to say, Matzke doesn’t tell us where Meyer allegedly says this — because he never provides pages numbers for the quotes he attributes to Meyer.

In the end it’s hard to reconcile Matzke’s tone of intellectual superiority with his sloppy scholarship. But, of course, the issue of real interest here is not Nick Matzke. It is the book he supposedly reviewed and refuted, but in fact did not. And since he did not respond to the central arguments of the book that Stephen Meyer actually wrote, readers curious about Darwin’s Doubt would do well to ignore Matzke’s advice. Get the book, and by all means, spend some time with it and read it for yourself.