Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Physics, Earth & Space

Physics, Earth & Space

Dennis Prager Explains Why Some Scientists Embrace the Multiverse

At National Review Online, popular talk radio host Dennis Prager has a nice article titled “Why Some Scientists Embrace the ‘Multiverse’,” in which he reports on a recent scientific conference he attended:

It was clear that the scientific consensus was that, at the very least, the universe is exquisitely fine-tuned to allow for the possibility of life. It appears that we live in a “Goldilocks universe,” in which both the arrangement of matter at the cosmic beginning and the values of various physical parameters — such as the speed of light, the strength of gravitational attraction, and the expansion rate of the universe — are just right for life. And unless one is frightened of the term, it also appears the universe is designed for biogenesis and human life.

After citing scientists who laud the evidence for fine-tuning — people like Gerald Schroeder (PhD from MIT, where he later taught physics), Michael Turner (astrophysicist at the University of Chicago and Fermilab), Paul Davies (professor of theoretical physics at Arizona State University), Roger Penrose (professor of mathematics at Oxford), and Steven Weinberg (a Nobel Prize winner in physics, and anti-religious agnostic) — Prager concludes that “[u]nless one is a closed-minded atheist (there are open-minded atheists), it is not valid on a purely scientific basis to deny that the universe is improbably fine-tuned to create life, let alone intelligent life.”

So why do some scientists embrace the multiverse? According to Prager, who is Jewish, it’s precisely because they want to avoid the conclusion of design:

They have put forward the notion of a multiverse — the idea that there are many, perhaps an infinite number of, other universes. This idea renders meaningless the fine-tuning and, of course, the design arguments. After all, with an infinite number of universes, a universe with parameters friendly to intelligent life is more likely to arise somewhere by chance.

Prager rejoins:

But there is not a shred of evidence of the existence of these other universes — nor could there be, since contact with another universe is impossible.

Therefore, only one conclusion can be drawn: The fact that atheists have resorted to the multiverse argument constitutes a tacit admission that they have lost the argument about design in this universe.

The evidence in this universe for design — or, if you will, the fine-tuning that cannot be explained by chance or by “enough time” — is so compelling that the only way around it is to suggest that our universe is only one of an infinite number of universes.

The great irony of the multiverse, of course, is that it doesn’t really help materialists escape the problem of cosmic fine-tuning. In order to render their postulations of multiple universes plausible, physicists have had to formulate various speculative cosmological theories involving hypothetical “universe-generating” mechanisms.

But universes won’t multiply without good reason. Thus, these “universe generating” mechanisms themselves require prior fine-tuning as a condition of their generating universes. And so, even taken on their own terms, these multiverse theories do not ultimately explain away fine tuning.

There’s another serious problem with the multiverse hypothesis, as we explain in Discovering Intelligent Design:

Another danger of “multiverse thinking” is that it would effectively destroy the ability of scientists to study nature. A short hypothetical example shows why.

Imagine that a team of researchers discovers that 100% of an entire town of 10,000 people got cancer within one year — a “cancer cluster.” For the sake of argument, say they determine that the odds of this occurring just by chance are 1 in 1010,000. Normally, scientists would reason that such low odds establish that chance cannot be the explanation, and that there must be some physical agent causing cancer in the town.

Under multiverse thinking, however, one might as well say, “Imagine there are 1010,000 universes, and our universe just happened to be the one where this unlikely cancer cluster arose — purely by chance!” Should scientists seek a scientific explanation for the cancer cluster, or should they just invent 1010,000 universes where this kind of event becomes probable?

The multiverse advocate might reply, “Well, you can’t say there aren’t 1010,000 universes out there, right?” Right — but that’s the point. There’s no way to test it, and science should not seriously consider untestable theories. Multiverse thinking makes it impossible to rule out chance, which essentially eliminates the basis for drawing scientific conclusions. (p. 59)

Given a choice between destroying the logical basis for doing science, or inferring design, it seems that some scientists opt for the multiverse.

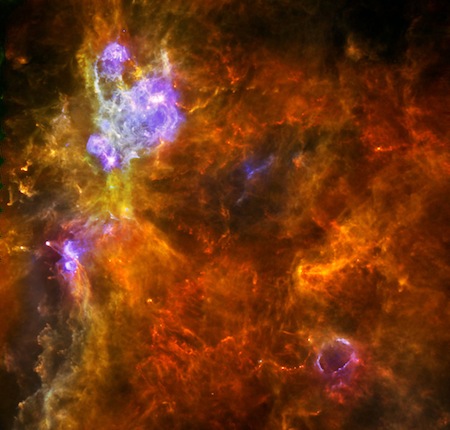

Image credit: ESA/PACS & SPIRE consortia, A. Rivera-Ingraham & P.G. Martin, Univ. Toronto, HOBYS Key Programme (F. Motte).