Nature Reviews Berlinski on Euclid

Our friend and colleague David Berlinski gets an enviable review in Nature for his new book The King of Infinite Space: Euclid and His Elements.

Fifty years might be a triumphant span for today’s textbooks. Euclid’s Elements is still fresh after 2,300. As mathematician David Berlinski writes in this pared and elegant homage to the peerless geometer and his magnum opus, the influence of Euclid’s axiomatic system remains vast. Berlinski unpacks the axioms, propositions and proofs along with their passage through history — from their influence on Copernicus and Bertrand Russell (who called his encounter with Elements “as dazzling as first love”) to the non-Euclidean world that sprang open in the nineteenth century.

See also the review in The Weekly Standard. David Guaspari points out the second half of Berlinski’s book which ranges “beyond Euclid proper, the pace accelerating through discussions of geometry and algebra, non?Euclidean and Riemannian geometries, Gauss’s intrinsic curvature, Hilbert’s reformulation of Euclidean geometry, groups and fields (ordered Archimedean fields, to be precise), and whips past, at the speed of light, Felix Klein’s ‘Erlangen Program.'”

Non-Euclidean geometry always make me think of Lovecraft’s descriptions of alien landscapes and ruins:

[T]heir discovery is a fascinating episode of intellectual history. Euclid’s parallel postulate amounts to saying that, given a line and a point, exactly one line can be drawn parallel to that line through the point. (Euclid formulates it differently.) To succeeding generations, this seemed both “evidently” true and more complicated than Euclid’s other axioms. And centuries of futile effort were spent trying to prove it from the others. In the 19th century, Janos Bolyai and Nikolai Lobachevsky independently developed consistent and rich theories of “geometry” in which the parallel postulate is false. They made themselves at home in a new mental world — one that was, from some points of view, literally unthinkable. Euclid’s geometry had been the paradigm of certain knowledge. How could denying one of its basic principles lead to anything other than incoherence? What exactly was geometry true of?

Congratulations, David, on all this good and well-deserved attention!

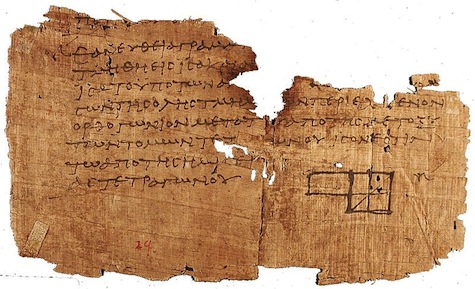

Image credit: Wikipedia, Oxyrhynchus papyrus (P.Oxy. I 29) showing fragment of Euclid’s Elements.