Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Design Inference vs. Design Hypothesis

In December 1994, I was in the middle of writing my philosophy dissertation for the University of Illinois at Chicago while also working on a masters of divinity degree at Princeton Theological Seminary. Visiting my parents in the Tucson area for the Christmas break, I was pondering what title to put on my dissertation. The dissertation focused on small-probability events used in chance-elimination arguments. Although the dissertation addressed some long-standing questions in the foundations of statistical reasoning, I also had my eye on bigger fish. Two years earlier, in the summer of 1992, I had spent several weeks with Stephen Meyer and Paul Nelson in Cambridge, England, to explore how to revive design as a scientific concept, using it to elucidate biological origins as well as to refute the dominant materialistic understanding of evolution (i.e., neo-Darwinism).

Such a project, if it were to be successful, clearly could not merely give a facelift to existing design arguments for the existence of God. Indeed, any designer that would be the conclusion of such statistical reasoning would have to be far more generic than any God of ethical monotheism. At the same time, the actual logic for dealing with small probabilities seemed less to directly implicate a designing intelligence than to sweep the field clear of chance alternatives. The underlying logic therefore was not a direct argument for design but an indirect circumstantial argument that implicated design by eliminating what it was not.

And so, on a bright December day in 1994 in Green Valley, Arizona, where my parents were retired, the term “design inference” hit me as capturing exactly what it is that this logic of dealing with small probabilities was attempting to accomplish. I wanted to avoid undue resonances with the design arguments of natural theology. At the same time, these were not pure eliminative arguments that simply told you that certain chance hypotheses were inadequate — design really was being implicated. I knew then that I had the title of my dissertation, a title that stayed in place as the dissertation was revised and then published with Cambridge University Press in 1998: The Design Inference: Eliminating Chance through Small Probabilities.

Go to Google, and you’ll find many, many references to the term “design inference” based on this coinage. There are even some amusing takeoffs on the term. “Design interference” appeared in a Christianity Today article that took Baylor University to task for pulling the plug on the intelligent design research center (the Michael Polanyi Center) that Baylor had previously asked me to found (for the details, go here). And, as a slip of the tongue, Ian Barbour, a science and religion scholar as well as Templeton Prize winner, even referred to it once as “the divine inference.”

The Logic of the Design Inference

Logic is always discursive, and this is true of the logic of the design inference. Logic has a starting point and an end point, and it follows a course or path from the starting to the end point. It thus has a direction, and one can speak of something being “upstream” or “downstream” from a particular point in an argument. The design inference, as I developed it, looks to a marker of design, what I call specified complexity or specified improbability, and from there reasons to a designing intelligence as responsible for this marker. If you think of brute complexity as simply a long random sequence of numbers, specified complexity is likewise a long sequence of numbers, but this time with a salient pattern (e.g., a Unicode representation of meaningful English text).

The details of specified complexity have been rehearsed at length in my written work and are readily available in print and online, so I won’t repeat myself here. What’s significant, however, for this discussion is the associated flow of logic, namely, FROM an information-theoretic marker of intelligence (specified complexity) TO an intelligent cause responsible for that marker (a designer). Specified complexity is an information-theoretic property exhibited by certain systems. A combination of mathematical and empirical factors characterizes it. Specified complexity is a sign. A sign of what? An intelligent cause.

A design inference having this logic seemed to me necessary for reinstating design in science since without it design would be scientifically undetectable — how can you detect something unless you know what you are looking for? In fact, this is a theme I had explored early on. One of the first things I ever wrote on design was for a 1991 conference at Wheaton College under the auspices of the Association of Christians in the Mathematical Sciences (one of its notable members was Donald Knuth). There I presented a paper titled “Detecting Design through Small Probabilities.” My book The Design Inference can be seen as an elaboration of the ideas in that early presentation.

What Good Does ID Do in Biology, Cosmology?

With a method of design detection in hand, the question arises what good this does in biology and cosmology. It’s one thing to infer design in archeological contexts where all the designers are humans. But if design is being inferred in biology or cosmology, who or what can the designer there be? It would certainly have to be an unevolved intelligence. The question then arises what explanatory benefit inferring such a designer can yield. Indeed, at the end of the day, what good is accomplished by ascribing some aspect of nature to the handiwork of a designer? Isn’t this, after all, what intelligent design is all about, namely, discovering aspects of nature that resist naturalistic explanation, inferring that they are the product of intelligence, and then invoking a nondescript designer as the intelligence responsible, who — wink, wink, nudge, nudge — we all know to be “the big G” or God?

This objection makes a valid point but also misses an important point. The valid point is that if intelligent design is simply about discovering instances of design and then saying “See, a designer did it,” ID would indeed be intellectually and scientifically substandard. But that is not what ID is doing. Let’s say that some particular piece of ID research infers that an intelligent designer is responsible for some aspect of nature. The objection, as stated (and it is widely stated thus), claims that ID’s work is finished once it attributes some aspect of nature to a designer. But in fact, ID’s work begins rather than ends with drawing a design inference, and this is where the objection misses the point.

Intelligent design, as the study of patterns in nature that are best explained as the product of intelligence (such patterns exhibit specified complexity), subsumes many special sciences, including archeology, forensics, and the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. None of these sciences concludes — full stop — with a designer. Rather, once design is inferred, a host of new questions arise. Given an archeological artifact, for instance, what is its function, what group of people was responsible, and what technologies did they have available? Given a death by unnatural causes, who was the perpetrator, how did he do it, and what might have been his motive? Given an intelligently produced radio signal from outer space, where are these aliens, what are they trying to communicate, and are we ever likely to encounter them directly?

More generally, once the possibility of design detection is raised, the following questions readily present themselves:

- Detectability problem — How is design detected? (answer: specified complexity)

- Functionality problem — What is a designed object’s function?

- Transmission problem — How does an object’s design trace back historically? (the search for narrative)

- Construction problem — How was a designed object constructed?

- Reverse-engineering problem — How could a designed object have been constructed?

- Perturbation problem — How has the original design been modified and what factors have modified it?

- Variability problem — What degree of perturbation allows continued functioning?

- Restoration problem — Once perturbed, how can the original design be recovered?

- Constraints problem — What are the constraints within which a designed object functions well and outside of which it breaks down?

- Optimality problem — In what way is the design optimal?

Each of these questions falls squarely within the natural and engineering sciences. Such questions are far from exhaustive, but they point up that once we know an intelligence has acted, inquiry proceeds by asking a new set of questions quite different from the questions we would ask if we thought the phenomenon in question were simply the product of blind material forces. So, suppose an intelligence is detected not just among human artifacts, as in archeology, but in cosmology and biology. Doesn’t this make intelligence a fundamental theoretical entity for science, on the order of a quark or black hole or quantum field? Yes it does. And such an entity might even be said to challenge scientific materialism and provide an opening for theism. That said, it goes too far to claim, as one commonly hears, that ID posits God as a theoretical entity for science.

Identifying the Designer

Critics of intelligent design think it somehow duplicitous that ID proponents don’t precisely identify the designer or intelligence that they infer from various patterns in nature. Instead, critics charge that they should come right out and admit that the designer is the God of their religious faith. Yet the problem is that nature by itself (leaving aside philosophy and theology) provides little evidence for the God of ethical monotheism. Nature gives us examples of great beauty and extreme ugliness, of gentleness as well as cruelty and indifference. Nor does it say anything about the revelation of God to Abraham or Moses, or in Christ. The intelligence that a design inference tells us is operating in nature may be the direct agency of the Judeo-Christian God. But even if the Judeo-Christian God is real, the intelligence we observe in nature may be acting through teleological surrogates (e.g., telic processes built into nature) that, via secondary causes, realize God’s purposes but don’t represent his direct activity.

To complicate things further, God is not the only option as the ultimate source of the intelligence we find in nature. It could be that nature is complete in itself, with no need for a personal transcendent God, and that its intelligence is intrinsic. How that could be and whether it is coherent are topics for the philosophy of religion. The point is that intelligent design does not posit God as a theoretical entity. Rather, it infers that intelligence acts in nature, and in the biological world in particular, yet without prejudice for the metaphysics or theology that might say who or what that intelligence is. This is not duplicitous. It is simply being honest about how far the evidence of nature can take us. Intelligent design can infer that a designing intelligence has been active in nature. Such an intelligence, simply in virtue of the tools that ID uses to study intelligence, will have to be characterized in highly generic terms. Identifying that intelligence with God will always require additional philosophical or theological moves extrinsic to ID.

A successful design inference applied to biology and cosmology would tell us that an intelligence has been active at the level of the universe as a whole and in biology in particular. Such an inferred intelligence could be one or many, organized hierarchically or decentralized, intrinsic to nature or transcending it, operating through a gradual creative evolutionary process or causing novel structures to magically materialize, etc. etc. The details of how this intelligence acts in the universe and should properly be conceived are logically downstream to the fact of this intelligence, if a design inference successfully and rightly infers this fact.

As far as any scientific theory of intelligent design is concerned, however, the intelligence or designer active in cosmology and biology does one key thing, namely, create novel information — and not just any information, but specified complexity. The term specified complexity has gotten a bad rap from some contemporary critics, as though the term is merely a magic phrase for covering our ignorance of how design inferences really work. But variations of the term specified complexity have been around now for fifty years, with even Richard Dawkins and Francis Crick seeing structures that are at once complex and specified as urgently requiring explanation.

Intelligent design therefore does not start with positing God as a theoretical entity for science. Rather it starts with finding specified complexity in nature and using this to infer that an intelligence is operating in nature, an intelligence especially implicated in cosmological fine tuning and various forms of biological complexity. What nature tells us about this intelligence, however, is quite limited and doesn’t nearly go the distance of a full-blown metaphysics or theology. In particular, one has to go outside science to make the identification of this intelligence with the God of religious faith. This, by the way, is entirely in line with a view that says science can provide evidence for a premise in an argument for God’s existence. Intelligent design treats specified complexity as evidence that an intelligence operates in nature. The claim that intelligence operates in nature can then be the premise of an argument for theism, for instance, one that treats the existence of God as the best explanation of that premise.

The logic of the design inference moves from a marker of intelligence (specified complexity) to an intelligence as causal agent responsible for that marker. The direction of this logic can, however, be reversed. Thus, instead, one can postulate an intelligence operating in nature and therewith formulate predictions and expectations about what one should find in nature if that postulate is true. The logic in this case takes the form of hypothetical reasoning, where a hypothesis is put forward and then its consequences are drawn out and the explanatory fruitfulness of the hypothesis is seen as a way of advancing science and giving credibility to the hypothesis. Stephen Meyer has taken this approach to design reasoning, treating it as an inference to the best explanation in which the hypothesis of design gains credibility because of its power in explanation.

Meyer is not alone. In River out of Eden, Richard Dawkins writes “The illusion of purpose is so powerful that biologists themselves use the assumption of good design as a working tool.” To be sure, Dawkins thinks that no design in biology is actual but only the outworking of blind natural forces “guided,” insofar as nature can guide anything, by natural selection. But what if natural selection is not up to the task? The recent ENCODE findings show Dawkins backpedaling from his claim as recently as 2009 (in The Greatest Show on Earth) that most human DNA is junk, having no function, and simply carried along as flotsam and jetsam by a sloppy evolutionary process. Yet now, in 2012, he claims that natural selection is a wonderful optimizer that makes DNA ultra-efficient (David Klinghoffer underscores this change of heart here at ENV). Dawkins’s special pleading is obvious, but the point to recognize is that if design — that is, real intelligence, and not just the designer-substitute of natural selection — makes better sense of biological complexity, then that commends the design hypothesis.

Design Inference, Design Hypothesis: Mutually Reinforcing Approaches

I titled this essay “Design Inference vs. Design Hypothesis,” which could suggest that the two approaches are opposed. But in fact, they reinforce each other. If a design inference provides good evidence for intelligence in nature, then we have all the more reason to suspect that a design hypothesis may be fruitful for science, in which case we should try it out. Likewise, if the illusion of purpose is as powerful as Dawkins claims and the assumption of good design is a fruitful scientific hypothesis, then we are in our rights to ask whether it is indeed an illusion and if there might not be good independent evidence of design in nature, evidence of the sort that a design inference might uncover.

Design inferences and design hypotheses both fall within the scientific theory of intelligent design. At the same time, design hypotheses function somewhat differently in that theory from design inferences. Design hypothetical reasoning embraces a pragmatism that is less evident in design inferential reasoning. Design inferential reasoning tends to be matter of fact, looking for clear indicia of design and drawing the appropriate inference. Design hypothetical reasoning, by contrast, is willing to posit hypotheses without, in the first instance, worrying whether they satisfy any canons of “scientific correctness.”

A pragmatic approach lets evidence go where it will and imposes as few limits on scientific inquiry and theorizing as possible. Such limits always derive from extra-scientific considerations anyway. There are, for instance, no scientific experiments or observations to tell us what constitutes science. Science is not in a position to define science. Notwithstanding, a pragmatic approach to science can clash with prior philosophical commitments, especially when these are held too ardently. In principle, pragmatism need not conflict with any prior philosophy. A prior philosophy might, for instance, say “This is the way the world is,” to which pragmatism could reply, “But it’s useful to think of the world as quite different for certain inquiries.”

Such pragmatism in scientific explanation has a long history. It even allowed Copernicus’ revolutionary hypothesis to be considered for decades without controversy. Unlike Galileo, who claimed that the earth actually does move around the sun, Osiander, Copernicus’s publisher of De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium, made sure, in the foreword, to stress that Copernicus’s theory provided one way of accounting for the movements of heavenly bodies but should not for that reason be interpreted as claiming that these were their actual movements. In other words, Copernicus’s theory was attempting to “save the phenomena,” matching theory to observation and thereby meeting a criterion for empirical adequacy known to the ancient Greeks. Osiander enabled Copernicus’ theory to keep peace with the Catholic Church in a way that Galileo could not, for Galileo claimed that the earth did not merely appear to rotate around the sun but actually did so. Thus, when Copernicus proposed his theory, given Osiander’s foreword, he could be viewed as a pragmatist describing what heavenly bodies appeared to be doing, yet without committing himself to the literal truth of this description.

Given such a pragmatic approach to explanation, it’s conceivable that an atheistic materialist might nonetheless embrace the design hypothesis. Such a materialist might, for instance, hold the following three positions:

- He might regard non-teleological theories of evolution as evidentially challenged and lacking compelling justification.

- He might consider intelligent design as a more fruitful (or at least equally fruitful) way of thinking about biological origins.

- And he might still reject that any god or intelligence stands behind nature.

What Intelligent Design Offers to a Materialist Atheist

Do any such atheistic materialists actually exist? New York University’s Thomas Nagel might be a case in point. In Mind and Cosmos, subtitled Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature Is Almost Certainly False, Nagel has this to say about neo-Darwinian evolution (the dominant materialistic account of biological origins) as it relates to intelligent design:

As I have said, doubts about the reductionist account of life go against the dominant scientific consensus, but that consensus faces problems of probability that I believe are not taken seriously enough, both with respect to the evolution of life forms through accidental mutation and natural selection and with respect to the formation from dead matter of physical systems capable of such evolution. The more we learn about the intricacy of the genetic code and its control of these chemical processes of life, the harder these problems seem…

In thinking about these questions I have been stimulated by criticisms of the prevailing scientific world picture from a very different direction: the attack on Darwinism mounted in recent years from a religious perspective [sic] by the defenders of intelligent design. Even though writers like Michael Behe and Stephen Meyer are motivated at least in part by their religious beliefs, the empirical arguments they offer against the likelihood that the origin of life and its evolutionary history can be fully explained by physics and chemistry are of great interest in themselves. Another skeptic, David Berlinski, has brought out these problems vividly without reference to the design inference. Even if one is not drawn to the alternative of an explanation by the actions of a designer, the problems that these iconoclasts pose for the orthodox scientific consensus should be taken seriously.

Such a pragmatic approach to intelligent design might appear to be resurrecting the discredited medieval notion of “double truth.” Back in the Middle Ages, some thinkers, such as Siger of Brabant, saw natural philosophy/science as telling us one thing about the world and metaphysics/theology the complete opposite. Thus, for these medievals, science (an Aristotelian science) taught that the world is eternal whereas theology (a Catholic Christian theology) taught that the world was created a finite time back. Yet rather than try to reconcile these opposing views, those advocating double truth were content to live with the tension, regarding both views as giving a true account of reality.

By contrast, pragmatism has no place for such double truths. That’s because pragmatism is not in the business of defining reality. It doesn’t say how the world is but how it might be useful to think of the world as being. If appearance and reality happen to match, so much the better. But pragmatism is limited only by imagination. And while logic may have laws, imagination does not, a fact that, ironically, weighs in favor of imagination’s importance for science, despite all the hype that science is preeminently a logical enterprise. As Einstein put it, “Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution. It is, strictly speaking, a real factor in scientific research.”

In effect, pragmatism can avoid outright contradiction with prior philosophical or religious commitments because it can always treat its constructs and theories as useful fictions (“pretend that the world is thus because it’s useful”). Even so, pragmatism faces an uphill battle with many scientists. Avoiding outright contradiction sets a low standard for what is scientifically acceptable. A more exacting standard for scientific acceptability is avoiding heresy, and pragmatism has a much harder time satisfying the heretic police.

Any set of prior philosophical commitments can lead its adherents, if those commitments are held with sufficient fervor, to persecute others, charging them with heresy and inflicting on them the appropriate penalties (dire consequences inevitably follow the charge of heresy). We see this today in the way prior philosophical commitments get used to invalidate intelligent design (recall Ben Stein’s Expelled). Atheistic materialism, for instance, doesn’t merely hold that nature is all there is and that it is composed entirely of material entities that operate on mechanistic principles. Typically it also comes wedded to a scientific realism that identifies science with our truest picture of the world.

Once atheistic materialism and scientific realism are both taken for granted, no design hypothesis can be valid. Intelligent design — in giving a picture of the world, even a hypothetical one, in which intelligence is presented not merely as an offshoot of blind evolutionary processes but also as a key causal power in life’s origin and subsequent development — then becomes scientific heresy. To find, for instance, evidence of design in DNA and the protein synthesis machinery that’s inside every cell would, in that case, merely betray a lack of understanding of the relevant laws and processes of nature. And how could it not, if atheistic materialism is true and science is our only reliable avenue to truth?

But is atheistic materialism true and how do we know it to be true? Without the possibility of detecting design (hence the need for the design inference to reinforce the design hypothesis), atheistic materialism becomes immune to evidence. In that case, it becomes a matter of first philosophy, which for many of its adherents it is. This, then, is where the design inference comes to the rescue of the design hypothesis, by rendering design in nature scientifically detectable. If you will, where design hypotheses appeal to scientific pragmatism, design inferences appeal to scientific realism, arguing that design works so well as a hypothesis because there are good independent reasons for thinking it to be real.

In an intelligent design research program, design inferences therefore become our starting point. This is especially so in a scientific culture so heavily invested in materialism, against which a design inference will prompt its more honest and self-aware members to admit that solid evidence exists of an intelligence operating in nature and not reducible to blind material forces (cf. Thomas Nagel). With this opening for design vouchsafed by design inferences, design hypotheses in turn receive the soil and rain with which to flourish. Such hypotheses, depending on the scientific insight and specific character of the proposals, may in turn get us to look for design in hitherto unsuspected places and thus lead to further design inferences, with design inferential reasoning and design hypothetical reasoning continually reinforcing each other and ratcheting up our knowledge of design in nature.

The Demise of “Junk DNA”: A Confirmed Prediction

What I’m describing here is not purely speculative. In 1998 I predicted on the basis of a design hypothesis that supposed “junk DNA” was in fact likely to have a function and that the term itself was really a misnomer:

Design is not a science stopper. Indeed, design can foster inquiry where traditional evolutionary approaches obstruct it. Consider the term “junk DNA.” Implicit in this term is the view that because the genome of an organism has been cobbled together through a long, undirected evolutionary process, the genome is a patchwork of which only limited portions are essential to the organism. Thus, on an evolutionary view, we expect a lot of useless DNA. If, on the other hand, organisms are designed, we expect DNA, as much as possible, to exhibit function.

The recent ENCODE results confirm my prediction and put paid to the useless and misleading term “junk DNA.” (See Casey Luskin’s review of ENCODE.)

In conclusion, design inferences and design hypotheses are mutually reinforcing. Within the theory of intelligent design, they have a symbiotic relationship. The logic in the two types of reasoning flows in opposite directions. In design inferential reasoning, one looks for markers of intelligence, notably specified complexity, and from there infers that an intelligence was responsible, which in turn prompts further questions about the nature of the design in question (what’s the function, what’s the history, how does it take advantage of existing designs, etc.). On the other hand, in design hypothetical reasoning, one presupposes a design hypothesis and uses it to generate predictions, expectations, and insights that advance our scientific understanding. On these twin pillars, the design inference and the design hypothesis, rests the scientific theory of intelligent design.

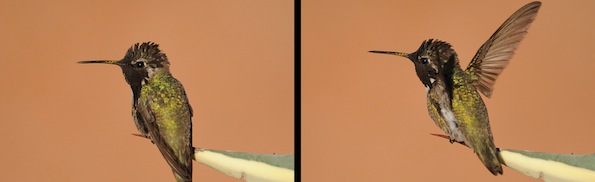

Image: JanetandPhil/Flickr, Costa’s Hummingbird (Calypte costae), Las Campanas Village, Green Valley, AZ