Evolution

Evolution

Human Origins

Human Origins

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Read Your References Carefully: Paul McBride’s Prized Citation on Skull-Sizes Supports My Thesis, Not His

While Paul McBride’s response to my Chapter 3, “Human Origins and the Fossil Record,” in Science and Human Origins ignores most of my arguments, one area where he does attempt a substantive rebuttal pertains to the history of hominin skull sizes. Even here, however, he again ignores some of my most important points regarding skull size in Homo, and cites a paper which supports my thesis rather than his.

While Paul McBride’s response to my Chapter 3, “Human Origins and the Fossil Record,” in Science and Human Origins ignores most of my arguments, one area where he does attempt a substantive rebuttal pertains to the history of hominin skull sizes. Even here, however, he again ignores some of my most important points regarding skull size in Homo, and cites a paper which supports my thesis rather than his.

There’s a reason why McBride focuses his response so heavily on skull sizes — it’s a rare characteristic for which there’s some consistent kind of a trajectory over time. But as we’ll see, the technical literature finds there is a “rapid change in hominin brain size,” with “punctuated changes” and a “saltation” in skull size that occurred with the appearance of the genus Homo. Believe it or not, that language came from a paper McBride cited in response to me. As one might surmise, that paper supports my thesis rather than his.

True to his civil tone, McBride “cordially” invited me to address cranial capacities, and this is what I hope to do in this article. I just wish he would also invite his fellow evolution bloggers like Nick Matzke and Richard B. Hoppe to behave in a “cordial” manner when discussing these issues. (Another double-standard?)

First, some preliminary matters.

Ignoring Authorities Backing My Arguments on Habilis

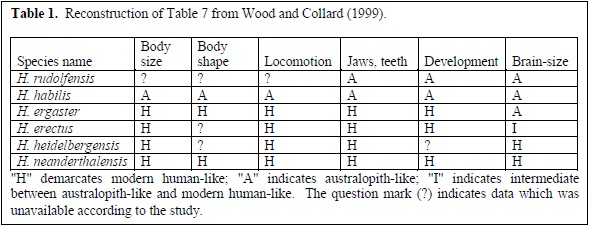

McBride writes: “Luskin, in fact, appears to reject that H. habilis belongs in Homo, referring to habiline specimens separately from ‘true members of Homo’.” McBride correctly describes my view, but he writes as if I invented this position arbitrarily to suit my wishes. That’s hardly the case, as this position is held by a number of other scientists. In that regard, McBride makes no mention of the strong authorities I cited in Science and Human Origins which support this view. Were it not for these papers and these authorities, I would never hold this position. Thus, my Chapter 3 cites a major review article in the journal Science by leading paleoanthropologists Bernard Wood and Mark Collard which suggested that habilis should be classified as a member of Australopithecus rather than Homo. They surveyed six traits and found that for each one, habilis fell within the australopithecines rather than Homo. A table summarizing their analysis is below:

Other credible sources I cited agree that habilis was unlike Homo. One paper from the Journal of Human Evolution found the skeleton of habilis was more similar to living apes than were other australopithecines like Lucy, and concluded: “It is difficult to accept an evolutionary sequence in which Homo habilis, with less human-like locomotor adaptations, is intermediate between Australopithecus afaren[s]is … and fully bipedal Homo erectus.” Likewise a paper from Nature I cited states: “Phylogenetically, the unique labyrinth of [the habilis skull] represents an unlikely intermediate between the morphologies seen in the australopithecines and H. erectus.” Again, McBride ignores these citations, and neither mentions nor addresses any of my reasons for arguing that habilis doesn’t belong in Homo.

One-Dimensional Thinking: The Pitfalls of Using Regression Lines to Claim “Gradual” Evolution

In arguing about skull sizes, McBride’s main approach is to rehash an old blog post by Nick Matzke from 2006, where Matzke was commenting on a paper I had published on human origins in 2005. Citing a paper by Henneberg and de Miguel (2004), Matzke noted that there’s an increase in the average size of hominin brain sizes over the past few million years. The paper had concluded that “all hominins appear to be a single gradually evolving lineage” with respect to cranial capacity. This got Matzke quite excited. Using the kind of rhetoric we’ve come to expect from Panda’s Thumb, Matzke argued that “creationists should be embarrassed and ashamed about the huge mass of evidence they ignore every time they fail to mention the stunning, overwhelming, transitional, gradual, nature of the hundreds of ancient fossil skulls that have been discovered.” He boasts that this is “an astonishing confirmation of evolution.” What was this “stunning” evidence? Matzke put up a chart showing hominin cranial capacities over the last few million years, with a nice, smooth regression line fit to skull sizes plotted against time. According to Matzke, this is supposed to show hominin cranial capacity increasing in a “gradual” fashion.

Matzke’s mistake is that a regression line can be fit to many types of data sets — including data that shows “gradual” change, but also including data that shows abrupt, rapid, and/or punctuational change. Sang-Hee Lee and Milford Wolpoff make this point compellingly in a 2003 article in Paleobiology, writing that “although changes in cranial capacity may be plotted against time, a trend line fitted to the bivariate distribution on the basis of regression is misleading.” Why is it misleading? Precisely because a trend line alone — the kind that Matzke waves triumphantly — doesn’t tell you whether the change in cranial capacity was gradual or punctuated:

However, whether brain size increased with statistical significance is not at issue here: there is no question that brain size increased over time. What we want to know is whether there was a change in the underlying process of change, and this cannot be answered with statistical rigor by fitting a single linear model for all the data points over time. For example, regression cannot be relied on to distinguish between a pattern of punctuated equilibrium and a gradual, constant change, because both of these could produce best-fitting trend lines with similar statistical attributes. This prevents us from using a regression method to fit one line for all the data points in answer to our question about process.

(Sang-Hee Lee and Milford H. Wolpoff, “The pattern of evolution in Pleistocene human brain size,” Paleobiology, Vol. 29 (2): 186-196 (2003) (emphasis added).)

Godfrey and Jacobs (1981) also warn against using a regression line approach because it can miss “punctuational” change. Their critique of other authors who used regression line analyses led to the following noteworthy warning about how these methods assume, rather than test for, gradual evolution:

those that are inclined to reject the punctuational hypothesis for human evolution should not design mathematical “tests” of punctuationalism that have gradualist conclusions predicated by gradualist a priori assumptions!

(Laurie Godfrey and Kenneth H. Jacobs, “Gradual, Autocatalytic and Punctuatlonal Models of Hominid Brain Evolution: A Cautionary Tale,” Journal of Human Evolution, Vol. 10: 255-272 (1981).)

Thus, papers like Henneberg and de Miguel (2004) used a flawed analysis and do not conclusively show “gradual” change.

Godfrey and Jacobs come to the conclusion that there is evidence for punctuational change, whereas Lee and Wolpoff believe hominin brain size changes in a “gradual” manner. Clearly, there are different opinions out there on this question. The recent reanalysis by Shultz et al. (2012) investigates why there are different opinions, noting that when one reviews the literature, you see there have been “different inferences made about the process of hominin brain size changes” due to the “different methodologies have been used.” The authors write:

A number of proponents support gradualism, whereas others argue that there have been long periods of stasis in brain size followed by bursts of change, or that rates of change vary over time and space.

(Susanne Shultz, Emma Nelson and Robin I. M. Dunbar, “Hominin cognitive evolution: identifying patterns and processes in the fossil and archaeological record,” Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B, Vol. 367:2130-2140 (2012) (internal citations removed).)

Shultz et al. (2012) conclude that “One conclusion that all methods agree upon is that brain size has increased, but the tempo of those changes remains unresolved.” I’ll discuss this paper further below, since it shows a “rapid change in hominin brain size,” with “punctuated changes” and a “saltation” in skull size when Homo abruptly appeared.

Paul McBride’s response to me usually tried to maintain an objective tone. But he got so caught up in Matzke’s strong rhetoric about skull sizes–“creationists should be embarrassed and ashamed about the huge mass of evidence they ignore every time they fail to mention the stunning, overwhelming, transitional, gradual, nature of the hundreds of ancient fossil skulls that have been discovered”–that McBride called Matzke’s arguments “breathtaking.” I suppose that’s a fitting word when you realize that the regression line which so excited Matzke doesn’t tell you anything about whether the data shows gradual change.

So What if There Are Skulls of Intermediate Size?

I never found Matzke’s original 2006 Panda’s Thumb post to be worth much of a reply because it in turn responded to so little of my 2005 paper, and anyone who read my prior paper would see that this objection about the existence of intermediate skull sizes was addressed. I also discussed it in my recent chapter on the hominin fossil record in Science and Human Origins.

First, my chapter acknowledges that there are plenty of skulls of intermediate size — and that skull size increased abruptly about 2 my. As I wrote:

A 1998 article in Science noted that at about 2 mya, “cranial capacity in Homo began a dramatic trajectory” that resulted in an “approximate doubling in brain size.”103 Wood and Collard’s review in Science the following year found that only one single trait of one individual hominin fossil species qualified as “intermediate” between Australopithecus and Homo: the brain size of Homo erectus.104

So yes, there are lots of skulls of different sizes — some might call many of them “intermediate.” In fact according to some leading paleoanthropologists, this is the only trait for which there are intermediate examples in the hominin fossil record. As seen in Table 1 above, Wood and Collard’s review looked at six traits — and you can score brain size as the one trait for which they find fossils with intermediate characters. So instead of the score being 6 to nothing against Darwinian evolution, I suppose the score now is only 5 to 1. This is nothing new and I fully acknowledge it in my paper.

But how important is brain size as an intermediate trait? Though McBride tries to brush it off, my article addresses this topic as well:

However, even this one intermediate trait does not necessarily offer any evidence that Homo evolved from less intelligent hominids. As they explain: “Relative brain size does not group the fossil hominins in the same way as the other variables. This pattern suggests that the link between relative brain size and adaptive zone is a complex one.”105

Likewise, others have shown that intelligence is determined largely by internal brain organization, and is far more complex than the sole variable of brain size. As one paper in the International Journal of Primatology writes, “brain size may be secondary to the selective advantages of allometric reorganization within the brain.”106 Thus, finding a few skulls of intermediate size does little to bolster the case that humans evolved from more primitive ancestors.

[…]

Figure: Got a big head? Don’t get a big head. Brain size is not always a good indicator of intelligence or evolutionary relationships. Case in point: Neanderthals had a larger average skull size than modern humans. Moreover, skull size can vary greatly within an individual species. Given the range of modern human genetic variation, a progression of relatively small to very large skulls could be created by using the bones of living humans alone. This could give the misimpression of some evolutionary lineage when in fact it is merely the interpretation of data by preconceived notions of what happened. The lesson is this: don’t be too impressed when textbooks, news stories, or TV documentaries display skulls lined up from small sizes to larger ones.

McBride vaguely alludes to this discussion but frames it in the context of my supposed motives rather than actually evaluating the arguments and evidence I provide in support of my view.

In short, you shouldn’t be too impressed when Nick Matzke or someone else posts a graphic showing that skull size increased over the last couple million years. Definitely don’t be impressed by regression lines presented in the absence of any deeper analysis.

And what about the upward trendline? This too is as unimpressive as it is unsurprising. After all, between 2 and 4 million years ago, the primary hominins running around were small-brained australopithecines. Homo didn’t exist before 2 million years ago, but sometime after that it appeared abruptly, and thus after that time we see much larger brain sizes dominating the fossil record — much larger than the australopithecines which dominated before that time. So it’s no surprise that the average size of skulls increased. (And as we’ll see below, when it does increase, it occurs in “rapid” and “punctuated” fashion which implies “saltation.”) But the point is that when you look at the overall story of human evolution, it’s a lot more complicated than the sole dimension of skull size increasing steadily in one direction. There is an entire suite of traits that, taken together, uniquely characterize the first members of Homo, and skull size is just one of many. So finding that a single trait changes smoothly doesn’t really tell you much about whether Homo itself appeared in a gradual manner.

Again, my article addressed this point and showed that many complex traits characterized the revolution that occurred with the appearance of Homo:

[A] study of the pelvic bones of australopithecines and Homo proposed “a period of very rapid evolution corresponding to the emergence of the genus Homo.”107 In fact, a paper in the Journal of Molecular Biology and Evolution found that Homo and Australopithecus differ significantly in brain size, dental function, increased cranial buttressing, expanded body height, visual, and respiratory changes and stated: “We, like many others, interpret the anatomical evidence to show that early H. sapiens was significantly and dramatically different from… australopithecines in virtually every element of its skeleton and every remnant of its behavior.”108

McBride (and Matzke’s) objections to my chapter on this point are very unsophisticated. Evolution is much more complex than the sole dimension of brain size, and that dimension itself is of uncertain importance in determining intelligence. Yes it increases over time, but early Homo differed from the australopithecine apes by a lot more than just brain size. When Homo appears, it appears with a bang. As my chapter explains:

Noting these many changes, the study called the origin of humans, “a real acceleration of evolutionary change from the more slowly changing pace of australopithecine evolution” and stated that such a transformation would have included radical changes: “The anatomy of the earliest H. sapiens sample indicates significant modifications of the ancestral genome and is not simply an extension of evolutionary trends in an earlier australopithecine lineage throughout the Pliocene. In fact, its combination of features never appears earlier.”109

These rapid, unique, and genetically significant changes are termed “a genetic revolution” where “no australopithecine species is obviously transitional.”110 For those not constrained by an evolutionary paradigm, what is also not obvious is that this transition took place at all. The lack of fossil evidence for this hypothesized transition is confirmed by Harvard paleoanthropologists Daniel E. Lieberman, David R. Pilbeam, and Richard W. Wrangham, who provide a stark analysis of the lack of evidence for a transition from Australopithecus to Homo:

Of the various transitions that occurred during human evolution, the transition from Australopithecus to Homo was undoubtedly one of the most critical in its magnitude and consequences. As with many key evolutionary events, there is both good and bad news. First, the bad news is that many details of this transition are obscure because of the paucity of the fossil and archaeological records.111As for the “good news,” they still admit: “[A]lthough we lack many details about exactly how, when, and where the transition occurred from Australopithecus to Homo, we have sufficient data from before and after the transition to make some inferences about the overall nature of key changes that did occur.”112In other words, the fossil record provides ape-like australopithecines, and human-like Homo, but not fossils documenting a transition between them.

In the absence of fossil evidence, evolutionary claims about the transition to Homo are said to be mere “inferences” made by studying the non-transitional fossils we do have, and then assuming that a transition must have occurred somehow, sometime, and someplace.Again, this does not make for a compelling evolutionary account of human origins. Ian Tattersall also acknowledges the lack of evidence for a transition to humans:

Our biological history has been one of sporadic events rather than gradual accretions. Over the past five million years, new hominid species have regularly emerged, competed, coexisted, colonized new environments and succeeded — or failed. We have only the dimmest of perceptions of how this dramatic history of innovation and interaction unfolded…113Likewise, evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr recognized our abrupt appearance when he wrote in 2004:The earliest fossils of Homo, Homo rudolfensis and Homo erectus, are separated from Australopithecus by a large, unbridged gap. How can we explain this seeming saltation? Not having any fossils that can serve as missing links, we have to fall back on the time-honored method of historical science, the construction of a historical narrative.114As another commentator proposed, the evidence implies a “big bang theory” of the appearance of our genus Homo.115

McBride (and Matzke) don’t really engage with any of this evidence for the abrupt appearance of the new body plan represented by Homo other than to say (my paraphrase): “Well, we’ve got a skulls of intermediate sizes and can see skull sizes increasing over time, therefore I can ignore all this evidence of the abrupt appearance of Homo.” I supposed Matzke would add I should be “embarrassed and ashamed.” I’m not here to shame anyone. But critics need to deal with the fact that Homo represented a new type of hominin that had many distinct features, and a highly distinct combination of features, and that when it appeared, it appeared abruptly, without similar precursors. Simplistic diagrams or references to increases in the sole dimension of brain size don’t answer my argument.

Read Your Citations Carefully

As we saw, Nick Matzke got excited over Henneberg and de Miguel (2004) because it claimed “all hominins appear to be a single gradually evolving lineage” with respect to cranial capacity. This citation is also very important to McBride — but in an “Update” at the end of his review of my Chapter 3, he brandishes a new paper in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B — the aforementioned paper by Shultz et al. (2012).

It’s ironic that McBride positively cites Shultz et al. (2012), because McBride would seemingly disagree with the paper. McBride maintains there is a “lack of discontinuity” in the fossil record regarding hominin cranial capacity, but Shultz et al. (2012) finds evidence for “punctuational changes,” “saltation,” and “rapid change in hominin brain size.” The paper finds there was an abrupt increase in brain size in hominins corresponding to the origin of the genus Homo. This supports my thesis, not McBride’s.

Shultz et al. (2012) reviews many other papers that have investigated cranial capacity over time, and observes: “One conclusion that all methods agree upon is that brain size has increased, but the tempo of those changes remains unresolved.” The paper’s analysis is quite thorough and would seem to refute the strictly “gradual” interpretation of Henneberg and de Miguel (2004). The paper’s abstract then notes that a more sophisticated analysis reveals punctuated changes in cranial capacity:

Using both absolute and residual brain size estimates, we show that hominin brain evolution was likely to be the result of a mix of processes; punctuated changes at approximately 100 kya, 1 Mya and 1.8 Mya are supplemented by gradual within-lineage changes in Homo erectus and Homo sapiens sensu lato.

(Susanne Shultz, Emma Nelson and Robin I. M. Dunbar, “Hominin cognitive evolution: identifying patterns and processes in the fossil and archaeological record,” Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B, Vol. 367:2130-2140 (2012).)

Thus, there’s a “punctuated change” in skull size associated with the appearance of Homo about 1.8 mya. The abstract uses the word “gradual” but we learn later that this is not the normal trend for changes in brain size. As the paper states:

The consistent signal for step changes suggests that hominin brain expansion is not a single, gradual process but is rather characterized by step changes.

At one point the paper even characterizes these “step changes” as being equivalent to “saltations.”

Reading the rest of this paper, we find that there are periods of “rapid change in hominin brain size” — one of which corresponds to the appearance of the genus Homo. The paper states: “The first two step changes coincide with the appearance of early Homo,” and then offers this thesis statement at the beginning of the Discussion section:

We revaluated patterns of hominin brain size change and demonstrate that, rather than being a monotonic increase, hominin brain size increase is dominated by step changes with limited evidence for long-term gradual increases.

So this Shultz et al. (2012) actually argues that hominin brain size is “dominated by step changes” and while there is some gradual increase in cranial capacity, that evidence for longterm gradual increases is said to be “limited.”

If this paper had been published before our book was written, I surely would have cited it as another example of the abrupt appearance of a trait associated with the origin of Homo. In essence, this paper shows the opposite of what McBride is arguing — it shows that there is an abrupt increase in cranial capacity corresponding to the appearance of Homo.

In his haste to post an “Update,” McBride seemingly failed to read the citation carefully. And what of the “gradual and continous” change mentioned by this paper? Is this important for showing humans evolved from ape-like precursors? I’ll discuss that in the next section.

Small Homo erectus Skulls? Please Don’t Throw Me in That Briar Patch!

At one point in his review, McBride criticizes me for citing a lower-bound for Homo erectus cranial capacities which is higher than he thinks it should be, stating: “The average cranial volume of early Georgian H. erectus, dating to about 1.7 Mya, is 700cc (see Anton, 2003). Luskin’s source does not even acknowledge such small sizes, giving the lower bound for H. erectus as 850cc.”

I appreciate that McBride is checking my sources. That great if he found a source saying that there are erectus skulls that are a mere 150 cc smaller than the smallest erectus skull size I was aware of. I was just citing the sizes I found in my source — an authoritative textbook on human variation by Washington University of St. Louis anthropologist Stephen Molnar, Human Variation: Races, Types, and Ethnic Groups. If McBride found a skull size that was slightly smaller, that wouldn’t surprise me a bit since I also cited a credible scientific paper stating that modern humans can have cranial capacities as small as 800 cc — lower than the smallest size I found for H. erectus. In light of that fact, what should we make of the following comment from McBride?

For reference, modern humans have a cranial capacity averaging close to twice the average Georgian specimen.

McBride’s comment means very little. As I document in the book, there are modern humans with skull sizes ranging from 800 to 2200 cc. So we could easily rewrite McBride’s statement to say “some modern humans have a cranial capacity averaging close to three times of other modern human specimens.”

Does that mean some humans are evolutionary intermediates in lines that led to others? Does it mean some humans are less intelligent and represent evolutionary precursors to others? No, it means none of that. What it means is that there’s lots of diversity in skull size among modern humans, and skull size is a poor predictor of intelligence or evolutionary importance. This singular dimension is also a poor predictor of what species you belong to. So the fact that McBride found an erectus skull with 700 cc doesn’t do anything to bolster an evolutionary story.

But McBride apparently thinks otherwise. He ups the rhetoric when he writes:

This certainly leaves substantial ground to infer vast differences between us and early Homo in the one area most precious to Luskin. The problem for Luskin is there is no discontinuity in the fossil record between us and early Homo. Hence, we must conclude — contra Luskin — that there is no evidence of discontinuity in the fossil at the point where humans are singularly most likely to have acquired our truly modern humanness.

As we already saw, Shultz et al. found evidence of a discontinuity with regard to cranial capacity corresponding to the emergence of Homo. That aside, McBride’s comments are puzzling. He must think I tremble at the thought of hominin skulls in the range of 600-800 cc. He suggests I would be “uncomfortable” with such evidence. That’s both amusing and wrong. If he’d read my chapter more carefully, not only would he see that I fully acknowledges that cranial capacity is the one single trait for humans where we clearly find intermediates, but he’d also understand why I argued that that fact is of limited importance.

And as we saw above, when we look at average skull size over time, there are significant discontinuities in the fossil record — including a major one corresponding to the emergence of Homo. This is much more significant than finding a few skulls of intermediate size. There’s so much variation in this trait that one can always find skulls of intermediate sizes in the fossil record — perhaps there is even some limited evidence of gradual trajectories within species. But when you look at the record over time, you see abrupt jumps in average skull size — indicating that Homo had a starkly different average skull size which came on the scene abruptly, without gradual transitions from other forms. This evidence supports my thesis, not McBride’s.

Intelligent Homo erectus?

Finally, regarding the emergence of Homo, McBride writes, “An intellectually lacking H. erectus would seriously challenge all of what he has been trying to establish here — that there is an important discontinuity between humans (in the thoughtful, artful sense) and all else.” Largely inferred from tools presumed to have been fashioned by Homo erectus, our knowledge of the true intelligence of erectus is uncertain. However, as I recently discussed, there is intriguing evidence that erectus was capable of boatbuilding and seafaring over significant distances of water. Articles that have covered this story offer intriguing suggestions that erectus was highly intelligent:

- “To accomplish any seafaring journeys, Dr. Karl Wegmann of North Carolina State University says, ‘They had to have used some sort of boat, though we will probably never find preserved evidence of one.’ He acknowledges that this discovery weakens the idea that earlier hominids were landlocked. ‘We all have this idea that early man was not terribly smart. The findings show otherwise — our ancestors were smart enough to build boats and adventurous enough to want to use them.'” (Jorn Madsen, “Who was Homo erectus,” Science Illustrated (July/ August 2012), p. 23.)

- “Many researchers have hypothesized that the early humans of this time period were not capable of devising boats or navigating across open water. But the new discoveries hint that these human ancestors were capable of much more sophisticated behavior than their relatively simple stone tools would suggest. ‘I was flabbergasted,’ said Boston University archaeologist and stone-tool expert Curtis Runnels. ‘The idea of finding tools from this very early time period on Crete was about as believable as finding an iPod in King Tut’s tomb.'” (Heather Pringle, “Primitive Humans Conquered Sea, Surprising Finds Suggest,” National Geographic (February 17, 2010).)

We can only speculate about the intelligence of Homo erectus, but the likelihood remains that he was highly intelligent.

Conclusion

This has been a long article, but I hope it is instructive in showing how evolutionists deal with the fossil hominin evidence. As we’ve seen, multiple authorities recognize that our genus Homo appears in the fossil record abruptly with a complex suite of characteristics never-before-seen in any hominin. And that suite of characteristics has remained remarkably constant from the time Homo appears until the present day with you, me, and the rest of modern humanity. The one possible exception to this is brain size, where there are some skulls of intermediate cranial capacity, and there is some increase over time. But even there, when Homo appears, it does so with an abrupt increase in skull-size. And the earliest forms of Homo — Homo erectus — had an average skull size, and even a range of skull sizes, that are essentially within the range of modern human genetic variation. Citing smaller skull-sizes doesn’t change the fact that skull-size is of uncertain importance for determining intelligence.

The complex suite of traits associated with our genus Homo appears abruptly, and is distinctly different from the australopithecines which were supposedly our ancestors. There are no transitional fossils linking us to that group. If a few skulls of intermediate size is enough to convince McBride that humans shared a common ancestor with apes, so be it. But for me it’s insufficient–especially when there are so many other traits (possibly including skull size) which appear abruptly in a unique Homo body plan. My Chapter 3 in Science and Human Origins cites a wealth of scientific articles, books, and papers backing up my arguments — most of which are ignored by McBride. The lesson, I think, is that the gap in brain-size between Homo and the australopithecines will not be bridged by one-dimensional thinking.