Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Would Darwin, If He Rejoined Us, Be a Darwin-Doubter?

Thanks to the scholarship of Center for Science & Culture fellow Michael Flannery (Alfred Russel Wallace: A Rediscovered Life, Discovery Institute Press), we have explored here in some detail the historical what-if: What if Alfred Russel Wallace were alive with us somehow today? Would evolutionary theory’s co-discover be an advocate of intelligent design?

Thanks to the scholarship of Center for Science & Culture fellow Michael Flannery (Alfred Russel Wallace: A Rediscovered Life, Discovery Institute Press), we have explored here in some detail the historical what-if: What if Alfred Russel Wallace were alive with us somehow today? Would evolutionary theory’s co-discover be an advocate of intelligent design?

Given that Wallace ultimately embraced a proto-ID view, the answer seems to be an unequivocal yes.

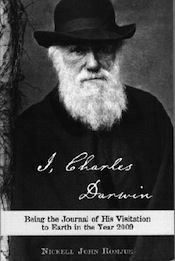

Far dicier, but more delicious, is the question of how Charles Darwin himself, if he rejoined the world, would respond to critiques of and alternatives to his theory. The question is irresistible and, to venture an informed speculative guess, calls as much for the mind of a novelist as that of a biologist. In a little book called I, Charles Darwin: Being the Journal of His Visitation to Earth in the Year 2009, history writer and novelist Nickell John Romjue gives it a whirl.

And with considerable success. Romjue imagines that in the great Anniversary Year, the man himself is sent by unnamed agents to return to life and look around a little. Romjue smartly elides the mechanics of the transition and instead has Darwin appear to his own surprise, with nearly unlimited access to modern scientific information, from archaeological digs to that “magical research tool,” the “worldwide web.”

Immersed in his studies at a public library, Darwin at one point has to scare away a fellow library patron to get access to a computer station.

When I hovered invisibly but too close over the shoulder of a fellow at this computer instrument, my shortened bristly beard managed to brush his neck, sending the poor man from the place screaming. Cancelling out the pornographic images (!!) he was watching, I went right to work.

Such realistic details of 21st-century life to one side, and with a decent mimic’s way with Darwin’s own quaint writing voice, Romjue does a fine job of imagining the order of subjects in which Darwin might get caught up on contemporary science and social thought.

Probably he would first turn his attention to aspects of zoology, embryology and paleontology, fields that existed in his time; then to the development of evolution-fed materialist philosophies from Marxism to Freudian to Nazism; and finally to fields that the historical Darwin never dreamed of, notably genetics, the microbiology of the cell, and cosmic fine-tuning.

Romjue’s Darwin, for example, takes a second look at the Gal�pagos finches, perceiving now that “Natural selection here was an oscillating phenomenon. While species had evidently diverged, contingent on dry-wet weather cycles, they could apparently also merge, and indeed were doing just that.”

He realizes the circular logic of inferring homology from common ancestry only to immediately pivot and infer common ancestry from homology. The enigma of the Cambrian explosion remains, Darwin also sees, as much a mystery in our time as in Darwin’s.

He mourns the evolution of his own idea in the hands of Stalin, Lenin, Mao and, most horrific of all, Hitler.

Man to Overman, to demigod, to embodiment of highest moral authority in an accidental, Godless universe, apogee of evolution, killer of his devalued “nonhuman” fellowmen in extermination camps and chambers by the scores of millions — men, women, beautiful children and, yes, babies in the womb. Beast to beast in the most advanced of all centuries and eras. History weeps.

Moving along and bringing him current with the most up-to-date lines of thought among Darwin doubters, Darwin confronts the problem of biological information:

How can a thing that has no physical organic reality originate, evolve — as I declared all life to have evolved from what I believed was a primordial single cell — across life’s great divisions through genera, orders, classes to phyla? As one of your scientists has lately said: the DNA molecule is the medium, but it is not the message.

In an exercise like this, there is always the peril of descending to hokum. Romjue avoids the danger. His conclusion, in which Darwin meets two of his own possible biological descendants, is sweet and in fact moving, framed by a discussion of the evolution, or miraculous eruption, of the capacity for love.

Self-anointed Darwin defenders won’t buy the takeaway lesson — that Darwin, given the fullness of the evidence of science that he never knew, would come to reject his own theory. You’ll have to read Romjue for yourself and decide. But on this point, there’s a highly relevant difference between the great man and his latter-day saints.

Modern Darwinists are distinguished by an almost unanimous refusal to answer the best arguments ranged against their precious theory. A coward like Jerry Coyne or Richard Dawkins or PZ Myers is content to offer cheap mockery of Biblical creationists, while occasionally setting up superficial drive-by jobs supposedly devastating to non-creationist “IDiots.” But almost never do Darwin apologists dare to take up the burden of responding to ID’s serious scientific challenges, as presented in serious forums by ID’s own scientists and theorists.

This is very different from Charles Darwin, who in his major books and other writing did grapple directly with the hardest challenges to his ideas. He sought them out. He candidly admitted difficulties where he perceived them.

He deserves better than Coyne/Dawkins/Myers — boy, does he. An honest man and a brave one, Darwin, as brought back to life by Mr. Romjue, might well rethink the revolution he sparked.