Evolution

Evolution

Life Sciences

Life Sciences

Sea Monkeys Are the Tip of the Iceberg: More Biogeographical Conundrums for Neo-Darwinism

In my previous post responding to the National Center for Science Education, I observed that the origin of South American monkeys (platyrrhines) is a striking example of a discontinuity between evolution and biogeography. As I observed at the end of that post, which was adapted from “The NCSE’s Biogeographic Conundrums: A Defense of Explore Evolution‘s Treatment of Biogeography“:

the NCSE was not quite accurate when claiming that “By comparing macroevolutionary patterns between different groups, we find that the same patterns repeat. This strongly suggests that the same forces drove the diversification of those different groups.” The truth is that whenever oceanic “sweepstakes” dispersal is required, we find an exception to expected neo-Darwinian rules of biogeography. And as will be seen in my next post, there are so many exceptions that one might reasonably question whether the inviolable neo-Darwinian rule of universal common ancestry is supported by biogeography.

When proponents of neo-Darwinism “speculate” about the “luck” and “chance” needed to explain this “amazing” phenomenon and “challenging” biegeographical data, it’s clear that they are lacking reasonable explanations. Yet rafting or other means of “oceanic dispersal” have been suggested to solve a number of other biogeographical conundrums that challenge neo-Darwinism, including:

- Lizards reaching South America78

- Large caviomorph rodents reaching South America79

- Bees arriving in Madagascar80

- Lemurs arriving in Madagascar81

- The arrival of other mammals in Madagascar, including the Tenrecidae (hedgehoglike insectivorous mammals), aardvarks, the hippopotamus, and the Viverridae (cat-sized carnivorous mammals)82

- Dispersal of salamanders across the western end of the Mediterranean83

- Dispersal of certain lizards across the western end of the Mediterranean84

- The origin of certain lizards in Cuba85

- The appearance of elephant fossils on “many islands,” which are said to have arrived by swimming86

- Dispersal of freshwater frogs across oceanic island chains87

- Certain frogs reaching Madagascar88

- The colonization of Anguilla by green iguanas89

- Appearance of certain South American insects90

- Dispersals of chameleons across the Indian Ocean91

- Origin of certain insects in Caribbean islands92

- The origin of mantellid frogs found on the island of Mayotte in the Comoros archipelago, despite the fact that “[a]mphibians are thought to be unable to disperse over ocean barriers because they do not tolerate the osmotic stress of salt water”93

- The spread of flightless insects to the Chatham Islands94

- The origin of indigenous gekkos in South America95

- Origin of crocodile distributions96

- The appearance of sloths in South America97

- The origin of a group of Australian rodents98

- The appearance of land mammals of the Mediterranean islands (also suggesting that “Hippos, elephants, and giant deer reached the islands by swimming”)99

- The origin of various land reptiles in Western Samoa100

- The presence of Crotalus rattlesnakes in Baja California101

Indeed, a review in 2005 by Alan de Queiroz wrote that “[s]triking examples of oceanic dispersal” include:

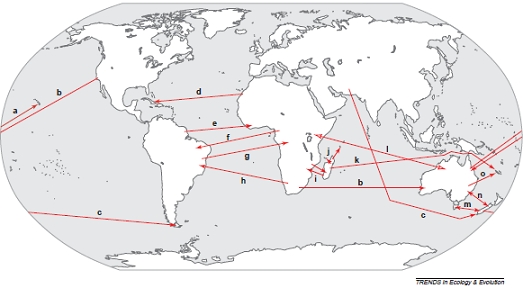

(a) Scaevola (Angiospermae: Goodeniaceae) three times from Australia to Hawaii; (b) Lepidium mustards (Angiospermae: Brassicaceae) from North America and Africa to Australia; (c) Myosotis forget-me-nots (Angiospermae: Boraginaceae) from Eurasia to New Zealand and from New Zealand to South America; (d) Tarentola geckos from Africa to Cuba; (e) Maschalocephalus (Angiospermae: Rapateaceae) from South America to Africa; (f) monkeys (Platyrrhini) from Africa to South America; (g) melastomes (Angiospermae: Melastomataceae) from South America to Africa; (h) cotton (Angiospermae: Malvaceae: Gossypium) from Africa to South America; (i) chameleons three times from Madagascar to Africa; (j) several frog genera to and from Madagascar; (k) Acridocarpus (Angiospermae: Malpighiaceae) from Madagascar to New Caledonia; (l) Baobab trees (Angiospermae: Bombacaceae: Adansonia) between Africa and Australia; (m) 200 plant species between Tasmania and New Zealand; (n) many plant taxa between Australia and New Zealand; and (o) Nemuaron (Angiospermae: Atherospermataceae) from Australia (or Antarctica) to New Caledonia.102

Figure 1 of De Queiroz’s paper contains a revealing map of the world covered in lines criss-crossing back and forth across oceans showing how many species must have traversed oceans to explain their distributions in locations unexpected by traditional biogeography:

(Reprinted from Trends in Ecology and Evolution, Vol.20(2), Alan de Queiroz, “The resurrection of oceanic dispersal in historical biogeography,” pages 68-73, (February 2005) with permission from Elsevier. Slightly resized to fit blog formatting.)

It seems clear that there are plenty of examples that contradict the NCSE’s simplistic picture of biogeography where the alleged “consistency between biogeographic and evolutionary patterns provides important evidence about the continuity … [that] would be expected of a pattern of common descent.” Somehow all of the above examples got left off the NCSE’s reply to Explore Evolution. There seem to be many more “biogeographic conundrums” than the NCSE is letting on.

References Cited:

[78.] John C. Briggs, Global Biogeography, pg. 93 (Elsevier Science, 1995).

[79.] Id. at 124.

[80.] Susan Fuller, Michael Schwarz, and Simon Tierney, “Phylogenetics of the allodapine bee genus Braunsapis: historical biogeography and long-range dispersal over water,” Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 32:2135–2144 (2005).

[81.] Anne D. Yoder, Matt Cartmill, Maryellen Ruvolo, Kathleen Smith, & Rytas Vilgalys, “Ancient single origin of Malagasy primates.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, Vol. 93:5122– 5126 (May, 1996); Peter M. Kappeler, “Lemur Origins: Rafting by Groups of Hibernators?,” Folia Primatol, Vol. 71:422–425 (2000); Christian Roos, Jürgen Schmitz, and Hans Zischler, “Primate jumping genes elucidate strepsirrhine phylogeny,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, Vol. 101: 10650–10654 (July 20, 2004).

[82.] Philip D. Rabinowitz & Stephen Woods, “The Africa–Madagascar connection and mammalian migrations,” Journal of African Earth Sciences, Vol. 44:270–276 (2006); Anne D. Yoder, Melissa M. Burns, Sarah Zehr, Thomas Delefosse, Geraldine Veron, Steven M. Goodman, & John J. Flynn, “Single origin of Malagasy Carnivora from an African ancestor,” Nature, Vol. 421:734-777 (February 13, 2003).

[83.] Michael Veith, Christian Mayer, Boudjema Samraoui, David Donaire Barroso, and Serge Bogaerts, “From Europe to Africa and vice versa: evidence for multiple intercontinental dispersal in ribbed salamanders (Genus Pleurodeles),” Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 31:159–171 (2004).

[84.] S. Carranza, D. J. Harris, E. N. Arnold, V. Batista and J. P. Gonzalez de la Vega, Phylogeography of the lacertid lizard, Psammodromus algirus, in Iberia and across the Strait of Gibraltar, Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 33:1279–1288 (2006).

[85.] Alan de Queiroz, “The resurrection of oceanic dispersal in historical biogeography,” Trends in Ecology and Evolution, Vol.20(2):68-73 (February 2005).

[86.] Richard John Huggett, Fundamentals of Biogeography, pg. 60 (Routledge, 1998).

[87.] G. John Measey, Miguel Vences, Robert C. Drewes, Ylenia Chiari, Martim Melo, and Bernard Bourles, “Freshwater paths across the ocean: molecular phylogeny of the frog Ptychadena newtoni gives insights into amphibian colonization of oceanic islands,” Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 34:7–20 (2007).

[88.] Miguel Vences, Joachim Kosuch, Mark-Oliver Rödel, Stefan Lötters, Alan Channing, Frank Glaw and Wolfgang Böhme, “Phylogeography of Ptychadena mascareniensis suggests transoceanic dispersal in a widespread African- Malagasy frog lineage,” Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 31:593–601 (2004).

[89.] Ellen J. Censky, Karim Hodge, & Judy Dudley, “Over-water dispersal of lizards due to hurricanes,” Nature, Vol. 395:556 (October 8, 1998).

[90.] C. Amedegnato 1993. African-American relationships in the Acridians (Insecta, Orthoptera). In: George W, Lavocat R, editors. The Africa-South America connection. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p 59–75, cited in Alain Houle, “The Origin of Platyrrhines: An Evaluation of the Antarctic Scenario and the Floating Island Model,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 109:541–559 (1999).

[91.] C. J. Raxworthy, M. R. J. Forstner, & R. A. Nussbaum, “Chameleon radiation by oceanic dispersal,” Nature, Vol. 415, 784–787 (February 14, 2002).

[92.] Nichols SW. 1988. Systematics and biogeography of West Indian Scaritinae (Coleoptera: Carabidae) (Florida, Mexico). Ph.D. thesis, Cornell University, cited in Alain Houle, “The Origin of Platyrrhines: An Evaluation of the Antarctic Scenario and the Floating Island Model,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 109:541–559 (1999).

[93.] Miguel Vences, David R. Vieites, Frank Glaw, Henner Brinkmann, Joachim Kosuch, Michael Veith and Axel Meyer, “Multiple overseas dispersal in amphibians,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, Vol. 270:2435–2442 (2003).

[94.] S. A. Trewick, “Molecular evidence for dispersal rather than vicariance as the origin of flightless insect species on the Chatham Islands, New Zealand,” Journal of Biogeography. Vol. 27:1189–1200 (2000).

[95.] Kluge AG. 1969. The evolution and geographical origin of the New World Hemidactylus mabouiabrookii complex (Gekkonidae, Sauria). Misc Pub Mus Zool Univ Chicago 138:1–78, cited in Alain Houle, “The Origin of Platyrrhines: An Evaluation of the Antarctic Scenario and the Floating Island Model,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 109:541–559 (1999).

[96.] Llewellyn D. Densmore III, and P. Scott White, “The Systematics and Evolution of the Crocodilia as Suggested by Restriction Endonuclease Analysis of Mitochondrial and Nuclear Ribosomal DNA,” Copeia, Vol. 3:602–615 (1991), as discussed in Alain Houle, “The Origin of Platyrrhines: An Evaluation of the Antarctic Scenario and the Floating Island Model,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 109:541–559 (1999).

[97.] Storch G. 1993. ”Grube Messel”andAfrican-South American faunal connections. In: George W, Lavocat R, editors. The Africa-South America connection. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p 76–86, cited in Alain Houle, “The Origin of Platyrrhines: An Evaluation of the Antarctic Scenario and the Floating Island Model,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 109:541–559 (1999).

[98.] Simpson GG. 1953. Evolution and geography: an essay on historical biogeography with special reference to mammals. Eugene, OR: Oregon State System of Higher Education, cited in Alain Houle, “The Origin of Platyrrhines: An Evaluation of the Antarctic Scenario and the Floating Island Model,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 109:541–559 (1999).

[99.] Wilhelm Schüle, “Mammals, vegetation and the initial human settlement of the Mediterranean islands: a palaeoecological approach,” Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 20:399–412 (1993).

[100.] Gill BJ. 1993. The land reptiles of western Samoa. J R Soc N Z 23:79–89, cited in Alain Houle, “The Origin of Platyrrhines: An Evaluation of the Antarctic Scenario and the Floating Island Model,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 109:541–559 (1999).

[101.] Stewart SG. 1990. Karyotypes of six rattlesnake (Crotalus) taxa of Baja California and selected Gulf Islands. Ph.D. thesis, California State University, Dominguez Hills, cited in Alain Houle, “The Origin of Platyrrhines: An Evaluation of the Antarctic Scenario and the Floating Island Model,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 109:541–559 (1999).

[102.] Alan de Queiroz, “The resurrection of oceanic dispersal in historical biogeography,” Trends in Ecology and Evolution, Vol.20(2):68-73 (February 2005).